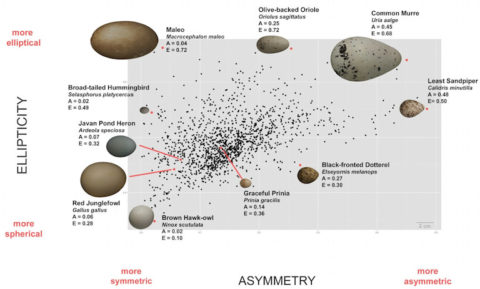

The shape of a bird’s eggs depends on how it flies, according to new scientific results. Sleek birds adapted to streamlined flight tend to lay more elliptical and asymmetric eggs, according to new research published today. The work cuckolds the classic theories about egg shape.

Broadly speaking, birds’ eggs can be ball shaped or elongated ovals. They can have one pointy end or be very symmetrical. Diet, nest space, cliff dwelling and other factors have all been scrambled to explain why some eggs are one shape and others another. Now, Joseph Tobias from Imperial College London, writing in the journal Science explains how he and his colleagues have measured the shapes of almost 50,000 eggs of 1,400 bird species. They analysed this hard-boiled data in the context of the bird family tree and species characteristics, such as nest type, clutch size, diet, and flight ability.

The researchers discovered there was a correlation between strong fliers and more elliptical and asymmetric eggs

The team found that murres, aka guillemots, (pictured above, prepping some eggs) which are fast, direct flyers that can also dive deep underwater had some of the most asymmetric eggs in the study. This was previously thought to be about precluding the egg rolling off a cliff edge into the sea below; an over easy theory. By contrast, owls – built for light, gliding flight – had some of the most spherical eggs, although the barn owls eggs are rarely sunny side up as it’s a dusk/night hunter.

“Bird eggs – previously described as ‘a miracle of packaging’ and ‘the most perfect thing in the universe’ – have fascinated people for millennia, yet only now are biologists beginning to crack the mystery of what makes some eggs more ‘egg-shaped’ than others,” says Tobias.

Lead author on the paper Mary Caswell Stoddard of Princeton University, adds: “In contrast to classic hypotheses, we discovered that flight may influence egg shape. Birds that are good fliers tend to lay asymmetric or elliptical eggs.”

The most obvious reason for this adaptation is simply that the sleeker fliers have less room in their abdomens and narrower oviducts for spheroidal  eggs. So, it’s a packaging problem for mother birds.

There’s no poaching of theories here, Tobias says that his team “found no support for the traditional ideas that variation in egg shape is caused by nest structure or placement on perilous cliff ledges, and instead found that egg size was related to the amount of calcium in the diet, and egg shape was best predicted by adaptations for powerful flight.”

Remember, if you don’t speak French one egg is never un oeuf…

“Avian egg shape: form, function and evolution” by M. C. Stoddard, E. H. Yong, D. Akkaynak, C. Sheard, J. A. Tobias, and L. Mahadevan, Science, (2017).