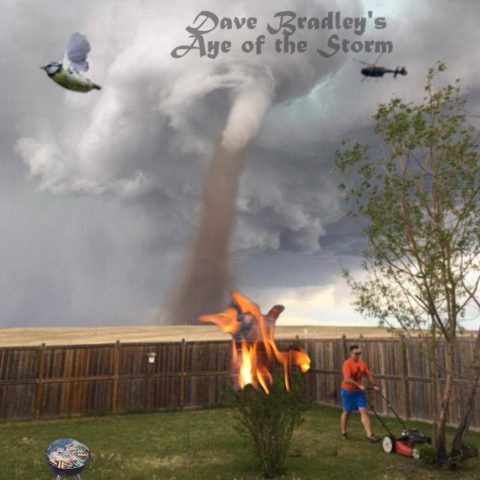

Everyone is talking about Cecilia Wessels’ photo of her husband Theunis mowing the lawn as a tornado looms ominously over the backyard at their home in Three Hills, near Alberta, Canada. My first thought was why is he trying to mow his tree, but my thought before that first thought was…surely, this is a missing 1970s prog rock album cover in the style of Hipgnosis or Hugh Syme…if there were flying pigs or a fire hydrant it could be a missing Pink Floyd or Rush album cover…

So, never one to not procrastinate when work needs to be done, I did a bit of a Thorgerson/Syme on the original photo with a few but and paste photos of my own – a blue tit, a police helicopter, a barbecue and some barbecue flames. I thought a nice title for my next foray into Geordie prog would have to be called “Aye of the Storm”.

And now the science(ish) bit: Tornadoes are rapidly rotating columns of air in contact with both the ground and cloud above. Stormchasers and others often refer to them as twisters or whirlwinds. Tornadoes often develop from a class of thunderstorms known as supercells. Supercells contain mesocyclones, an area of organized rotation a few kilometres up in the atmosphere, usually between 2 and 10 km across. They can be very destructive given that windspeeds within can reach 480 km/h. Other tornado-like phenomena include gustnado, dust devils, fire whirls, and steam devils. All great titles for the songs on the album.