Why does the public no longer trust science?

The first response to my question was from user J Pegues, a self-described CEO-level consultant in the US. Pegues, who in one sense ignited the flames, but also emphasised that people do not distrust science, instead they distrust the US government:

The first response to my question was from user J Pegues, a self-described CEO-level consultant in the US. Pegues, who in one sense ignited the flames, but also emphasised that people do not distrust science, instead they distrust the US government:

Who don’t people trust? Our lame federal government. People don’t even listen any more to what government spokespeople, including the president, say because they have lied to us, instituted policies aligned with their own myopic beliefs, and undermined every ideal the United States has stood for 230 years. Don’t confuse people’s lack of trust in the federal government, its hacks, and policies against the advancement of science with lack of trust in science.

Bryan Webb a marketing consultant in Canada suggested that Pegues is right on target:

We do not believe governments who have their own agenda which in general is not for the good of the people although their words (promises) at election time try to tell us another set of lies.

Uli Hofer, of Owl Database Applications, based in Canada, was the first to respond more directly to my question in the way that I had hoped LinkedIn users would with a point regarding the current media frenzy surrounding almost every scientific paper that appears these days:

A lot of what’s going on in today’s science is way over an average person’s head (astronomy, nuclear science, genetics, etc.). It is not possible to gauge the different points of view in a scientific discussion. The media, in constant pursuit of hot news, report on every scientific paper they can get their hands on. Way too often, these reports are reduced to ‘headlines’. And don’t kid yourself, political correctness governs science too. How often has the public heard about a wonderful new thing that is absolutely safe, that disappeared a short time later because it wasn’t?

Geoff Charlwood of Clinical Informatics at Pharmaceutical Profiles Ltd of Nottingham, England, suggested that there is something in the science and government issue and claimed that people do on the whole trust the government Chief Scientist of the day, in much the same way that they trust the Bank of England on interest rates and trust reports coming from the Chief Inspector of Prisons. Even though they may make mistakes, they are usually honest ones, he says:

They demonstrably maintain their independence from political considerations. On the occasions when such people overtly bring an agenda to their job, trust declines.

Walt Wallgren, a partner at Solid Ground Investments in San Francisco, had a fairly contrary view in that he believes the problem lies not with science but with scientists themselves:

If the scientific method is rigidly applied and results are unemotionally reported, science and scientists are on a firm footing.

He points out that scientists are people too. “They all have their own beliefs and ideas and they hate to be wrong just like everybody else. There are just as many pre-conceived beliefs in the scientific world today as there are in the pulpit. And, I believe that many of them are opposite to what religion teaches just to try to prove religion wrong.” He adds several examples from nutrition and health, global warming and even fundamental physics:

The distrust of science comes from too many purported scientists trying to get the data to fit the hypothesis and selling the idea to the general public. If you don’t like the answer, change the question make the answer fit your position. After all, studies have proven that you can prove anything with studies.

Software architect Brian Conner from the Greater San Diego area admits his gut feelings pertain only to US residents:

I doubt that much of the public understands and respects scientific principles. Though the basics of the scientific method is taught in school in the US I don’t know many people who really understand its importance. Lack of understanding leads to a situation where the public cannot distinguish between “good science” and “bad science.”

David Evans, a Multimedia Designer at the Science Museum of Minnesota, on the other hand, suggests that science will always be used to promote greed, and that is what breaks the promise that the big word Science has to offer.

Universities are always looking at how the results of scientific inquiry can be adapted to profitable results in the Real World. Scientific inquiry gets steered to businesses that copyright the results, and charge money for the opportunity to use the results, even after the public has paid for the scientific inquiry through grants based on taxes. How can you trust greed?

Graduate student Herman Van Wietmarschen of Leiden University also emphasises that science is not as neutral as one might believe, adding that scientific work has many social, ethical and often also economic aspects closely interwoven with it:

No scientific finding ever finds its uses to the public without a widespread network of other actors. Usually money needs to be found to develop the technology, interest of some companies needs to be found.

Robert Poulk, a network troubleshooter based in Seattle also points out that what happens between scientific discovery and their presentation:

We live in an advertising-driven world; content is presented not based on the public’s need to understand but on the advertisers’ need to get our attention, and they get it using classic bait-and-switch.

Information manager Christopher Goh suggested that my initial question gives in to the cynics and adds that there has never been more need of good science as there is today:

Science has come a long way from Copernicus and even Mendel, and those who want to seek out fact can do the right due diligence and sort through the raft of opinions quite easily. That pursuit of truth has and will always remain critical to man kind, and as long as science remains true to that pursuit, then all we can do is hope the right educational policies and frameworks will create a generation of people willing to seek it.

There were many other excellent responses to my initial question and follow-up qualification, which can all be read in their entirety on the LinkedIn site, here. You can also link up with any of the members who responded.

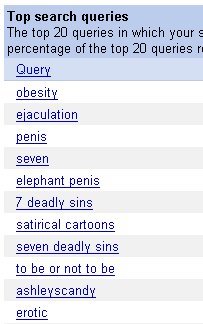

I posted the question above on the business and networking site LinkedIn as a test. It was a deliberately naïve and heavily loaded question, which I hoped would inspire fellow LinkedIn users to respond in depth, but on reflection I probably committed at least one of the seven deadly sins for scientists. It turned out to be quite a controversial question and inspired, if not quite hate mail, then quite a few flames, which I discussed in an earlier post about LinkedIn questions.

So, yes, you might say it has quite an inherent bias, suggesting as it does that the public is some kind of entity beyond science and that in this divide there is some obvious distrust.

I’m playing catch up, after some offline time last week (holidays, families, and illness), so today’s post is a grab-bag of the various items (mainly books) sitting in a large pile on my desk that I thought deserved a quick mention and a link or two for more information.

I’m playing catch up, after some offline time last week (holidays, families, and illness), so today’s post is a grab-bag of the various items (mainly books) sitting in a large pile on my desk that I thought deserved a quick mention and a link or two for more information.

The first response to my question was from user J Pegues, a self-described CEO-level consultant in the US. Pegues, who in one sense ignited the flames, but also emphasised that people do not distrust science, instead they distrust the US government:

The first response to my question was from user J Pegues, a self-described CEO-level consultant in the US. Pegues, who in one sense ignited the flames, but also emphasised that people do not distrust science, instead they distrust the US government: