I just can’t get you outta my head…is the usual thought when an irritatingly catchy pop song gets stuck on loop in your brain for days on end. A start-up company in East Anglia reasoned that this catchiness might be put to good use in helping people quickly learn a foreign language. Or, at the very least, a couple of dozen keyphrases that will help them get by while on holiday or a business trip abroad.

Programme creator Marlon Lodge found that background music seemed to help his language students remember phrases much better than simply hearing and repeating phrases by rote. Lodge teamed up with his brother Andrew and designed Earworms musical brain trainer (mbt) They reckon the system boosts language retention by up to 80%. I ripped the Earworms Italian CD to my mp3 player and listened every time I went for a run – in an effort to get fit and learn how to order pizza, a gelato, and a cappucino when we went on holiday this year.

It works. Very well. I’d done Spanish and French at school and Italian isn’t so different, but the earworms gave me the necessary extra to be able to confidently book a table, order food and drinks, and find out why the return flight got delayed so badly.

The system uniquely anchors foreign words and phrases into long term memory by hooking them to music. The company reckons it could provide a learning breakthrough for people with poor sight, dyslexia, or attention deficit problems by taking away the need to concentrate on reading phrase books and other academically based language courses.

‘Many people are reluctant to begin learning something new after they leave school, but as Mark Twain once said, ‘My education started the day I left school.’ Earworms is very much about giving people an easy handle on learning, and what easier way to learn than simply by listening to music, something we all enjoy?’ Lodge says.

The program is available for French, German, Greek, Italian, Spanish, and now Mandarin Chinese. More information at www.earwormslearning.com. It would be good to see some solid scientific research on how this system works, perhaps a functional MRI study showing the language centres in the brain lighting up more brightly with music rather than without. I’ll cover any such developments on spectroscopynow.com

Anyway, I just ordered the Spanish disc for next year’s holiday and they sent me Mandarin Chinese too…so, maybe I should think about going a little further afield.

Ciao for now!

John Mather of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and George Smoot of the University of California, Berkeley, share this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery of the blackbody form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation.

John Mather of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and George Smoot of the University of California, Berkeley, share this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery of the blackbody form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation. I received a press release today from a US company addressing me by name and asking me whether I’d like to write about nanocardiology. Apparently, the company has a nanotech product in pre-clinical trials that cleans up arterial plaques. The putative product from St Louis company Kereos is based on endothelial alpha-v-beta-3 integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles and can seek out markers for arterial plaques and help break them down.

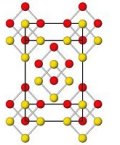

I received a press release today from a US company addressing me by name and asking me whether I’d like to write about nanocardiology. Apparently, the company has a nanotech product in pre-clinical trials that cleans up arterial plaques. The putative product from St Louis company Kereos is based on endothelial alpha-v-beta-3 integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles and can seek out markers for arterial plaques and help break them down. Nature described this finding as “surprising, elegant, and entirely useless”. Well, the journal is half right. Solid elemental oxygen is not thought to exist anywhere on earth or even elsewhere in the universe under the immense pressures created by Malcolm McMahon and Paul Loubeyre. They and their colleagues put the squeeze on solid oxygen, which forms deep red crystals at above a million atmospheres. They used various techniques to determine the structure of this new material and found that oxygen atoms team up to form clusters of eight in the solid. A seemingly esoteric discovery you might think.

Nature described this finding as “surprising, elegant, and entirely useless”. Well, the journal is half right. Solid elemental oxygen is not thought to exist anywhere on earth or even elsewhere in the universe under the immense pressures created by Malcolm McMahon and Paul Loubeyre. They and their colleagues put the squeeze on solid oxygen, which forms deep red crystals at above a million atmospheres. They used various techniques to determine the structure of this new material and found that oxygen atoms team up to form clusters of eight in the solid. A seemingly esoteric discovery you might think. Is your browser so locked down that you can’t install any plugins or enable Java? Firewall refusing to cooperate with your molecules? Antivirus screaming at your structural efforts?

Is your browser so locked down that you can’t install any plugins or enable Java? Firewall refusing to cooperate with your molecules? Antivirus screaming at your structural efforts?