If you have even a passing interest in the natural world, you will have most likely heard the phrase “invasive species”. By definition, a deliberate or accidental release of a species to an area beyond its natural environment where it then multiplies and causes damage to that environment and the native wildlife that relies on it. I discussed the UK issue of invasive species briefly last year and in the context of Muntjac and Black Hairstreak butterfly too.

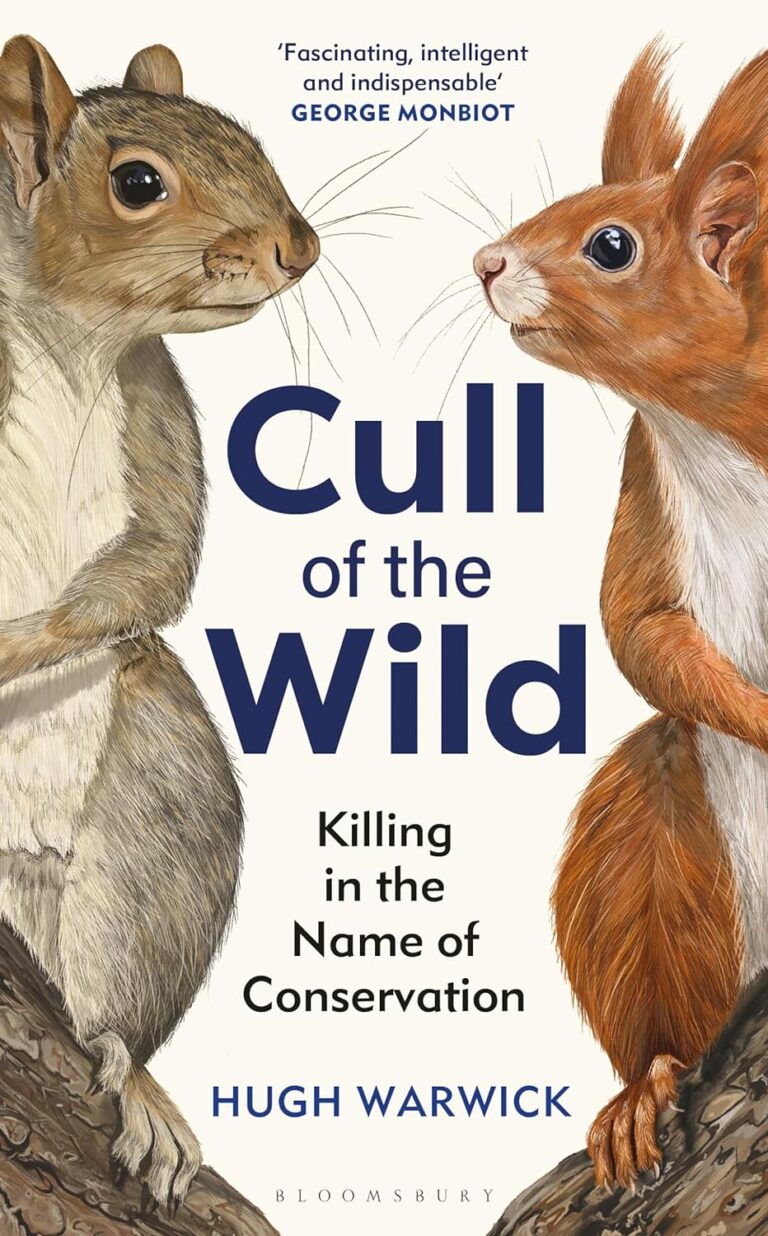

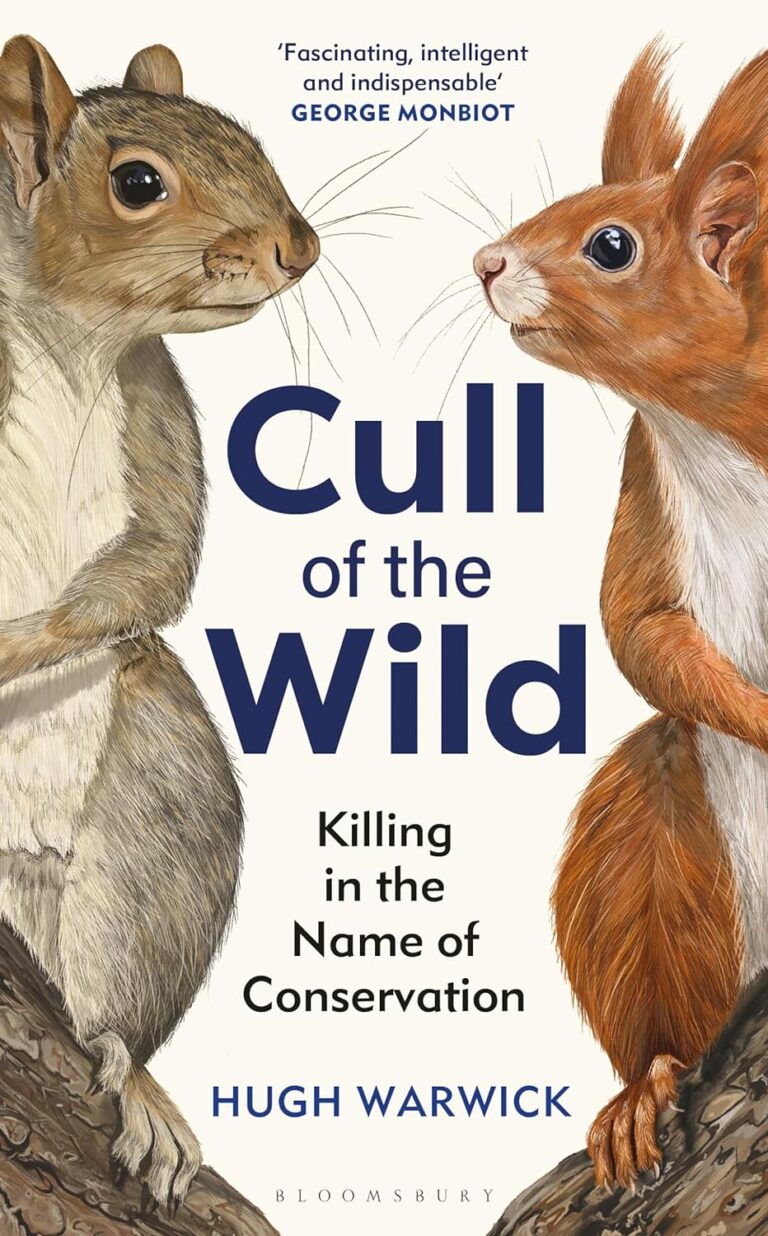

Ecologist and conservationist Hugh Warwick tackles the issue in much more depth in his latest book – Cull of the Wild. Warwick is, as most of us are, not keen on killing in the name of and recognises that the arguments and issues regarding the culling of invasive species where they threaten the very existence of native species and ecosystems are still very complicated.

In Cull of the Wild, he discusses how different approaches to control have been tried worldwide. The grey versus red squirrels, the cane toads in Australia, rats, even Pablo Escobar’s hippos and the Burmese python trade.

Warwick, a former vegan and now a self-confessed meat-eschewing vague-an, points out that millions of animals are killed, or culled, every year in the name of conservation, invasive species, feral populations, domestic animals. Sadly, much of this killing is cruel and essentially unregulated. To quote from Warwick’s introduction:

“We deserve an honest conversation about conservation. To do that we need to establish one very important point. Conservation, wildlife management, and the ecology that underpins them both, is really complicated. Add to this one more variable: people with differing perspectives. Now, it becomes close to impossible to solve the very real problems with which we are confronted. Complicated problems rarely have simple solutions…”

There are, we learn, no absolutes. Each invasive case has nuance where humans have destroyed habitat and the native species that once filled a niche are long gone, an incomer might fill that space and become prevalent. It might be that the new species brings benefits to that environment, perhaps reducing plant overgrowth and opening up biodiversity that resurrects the habitat.

The beautiful Box-tree moth, Cydalima perspectalis, represents an interesting example of the kind of nuance we have to address. It arrived in the UK around 2007, presumably hitching a ride on imported Asian strains of box-tree, Buxus. Unfortunately, it has spread and thrived, ravaging decorative box hedges across southern England.

There is little that can be done to control this invasive species at this point in its history other than grubbing out its larval food plants, Buxus, and planting something else. Insectidal sprays are not the answer as they kill the native species too, pheromone traps are of limited use and while they kill some of the males there will always be another to fertilise the female’s eggs on one’s box hedge, and picking off caterpillars for, ahem, disposal, is not the most pleasant way to spend a lazy Sunday afternoon.

However, to talk of the lack of the nuance and the lack of absolutes, it’s worth noting that Blackbirds are starting to recognise the larvae of this moth as a rich food source. So, whereas the presence of the moth is essentially well-balanced in its native environment, there is hope that this might happen naturally here too.

It is unlikely that many of the problematic invasive species we must cope with will naturalise in that way, so there may well forever be a need to find ways to control them or live with them. Warwick offers much for our consideration of the nuances of invasion.