TL:DR – Barn Owls regurgitate pellets containing the indigestible bones and fur from their prey. It is possible to dissect these owl pellets and to find out what the owl has eaten from the debris.

Barn Owl (Tyto alba) hunting over Rampton, VC29If you have ever stopped to think about the gustatory habits of owls, then you have perhaps wondered what happens to all the bones and fur from the little creatures on which they predate after they eat them.

Well, avian digestive enzymes do not have the capacity to break down bones and fur and as the flesh and organs are digested those materials accumulate in the upper gastrointestinal tract forming a hairy bolus, a pellet, that ultimately the owl will regurgitate. A pellet forms after six to ten hours following a meal in the bird’s gizzard, its muscular stomach. Owls and other birds of prey bring up the indigestible material from the proventriculus, their glandular stomach. The pellet is thought not only to get rid of indigestible waste materials that would not pass downwards safely but also to scour parts of the digestive tract, including the gullet to remove detritus that might harbour pathogens.

Now, the experimental bit.

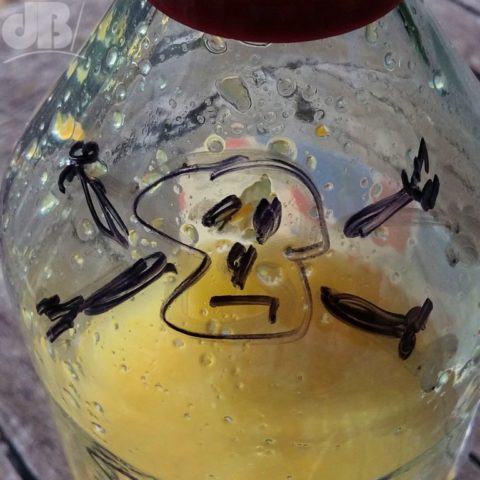

I collected an owl pellet (with the warden’s permission at WWT Welney on a recent visit and followed his instructions to soak the pellet in water for a number of hours and then to tease it apart to reveal the bones within its proventriculus, or glandular stomach.

After about an hour’s work I’d dissected the pellet to reveal a relatively large skull and separated lower jawbones of presumably a vole as well as various femurs, tibia, fibula, scapula, a few vertebrae and lots of rib bones, and perhaps another couple of much smaller skulls the extraction from the of the pellet I did not have the patience nor the equipment to pursue with the necessary care and attention to detail. I did not find any feathers nor insect exoskeletal parts or wings in this pellet. All the remains were rodent mammal.

Anyway, I am quite pleased with the produce harvested from my first owl pellet dissection. Mrs Sciencebase points out that she did the very same experiment as a biology student many moons ago.

Other birds, including the fish-eating, insect, and carrion-eating birds, grebes, herons, cormorants, gulls, terns, kingfishers, crows, jays, dippers, shrikes, swallows, and most shorebirds also produce pellets.