In optics (and thence photography, microscopy, and telescopy), the Airy disc is the optimally focused spot of light that a perfect lens with a circular aperture can make. It is the diffraction limit. It’s named after George Biddell Airy who wrote a detailed description although astronomer John Herschel had described the phenomenon when observing a bright star through his telescope.

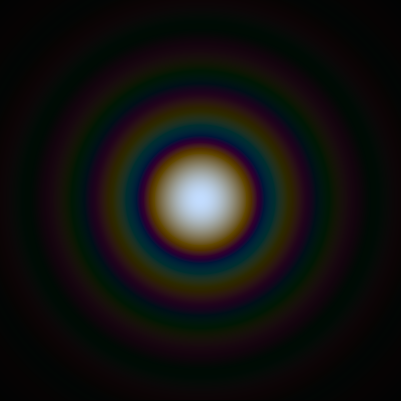

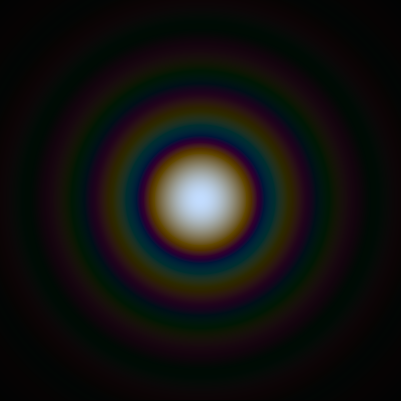

The Airy disk is a bright spot of light surrounded by concentric diffraction rings, all together they are referred to as an Airy pattern. The wavelength of the light and aperture size of the lens is critical to the size of the resulting pattern.

The Airy disk is a bright spot of light surrounded by concentric diffraction rings, all together they are referred to as an Airy pattern. The wavelength of the light and aperture size of the lens is critical to the size of the resulting pattern.

The old pinhole camera is at the diffraction limit, almost a point-like circular aperture. Due to this diffraction effect, the smallest point to which light can be focused with lens (or mirror) is the size of the Airy disk. Of course, lenses are not perfect and apertures are rarely circular, in a lens for an SLR and other types of camera they are usually made up of an array of six overlapping fins, (sometimes more, sometimes less. More means more circular and so better, and TV and cinematic film cameras often have 8 fins and so produce octagonal, rather than hexagonal bokeh. 8-finned cameras seem to have a much-improved image quality over more those with a more conventional 6-finned aperture.

Anyway, if Airy discs, light’s wavelength, and the lens aperture conspire to produce a diffraction limit, then it is pixel size in your camera’s sensor that “sees” this limit. It’s possible to calculate the diffraction limit. So, if your lens can be set to an aperture of f/2 (that’s the biggest aperture), the diffraction limit for green light with that aperture is about 2.7 micrometres. Dave Haynie discusses this in more detail here.

Now, f/2 is a low f-stop for most lenses. The Sigma 150-600mm with which I have photographed birds recently using my Canon 6D, can be set to f/5 when it’s at 150mm focal length, but only as low as f/6.3 at 600mm. That’s the biggest apertures it can manage. A larger aperture means more light in and exposure balanced against shutter speed and ISO number. My 90mm Tamron macro lens with which I have been photographing moths, has its biggest aperture at f/2.3.

Larger aperture means a smaller depth of field. The parts of the image that are closer or further away than the point at which you have focused the camera will be out of focus with a larger aperture (smaller f-stop). If you want a larger depth of field, then you need a smaller aperture, which means less light and critically from the perspective of sharpness, you begin to approach the diffraction limit. This occurs because of the Airy disc effect and how that coincides with the pixels on your camera’s sensor. To get a sharp image, you need the Airy Disc to be smaller than a pixel, realistically smaller than 2-3 pixels, explains Haynie. If you make the aperture bigger the Airy disc becomes bigger and so each perfect point of light will inevitably traverse a larger number of pixels, which is not what you want. Rather, you want each pinpoint of light from the object you are photographing to impinge on a single pixel.

This is where balance and compromise must come into play. A smaller aperture gives a larger depth of field, which is more important when doing close-up macro photography of small objects such as moths. So, you push the f-stop to a higher number to get a greater depth of field. Now, with small aperture, you are approaching that Airy problem. If you have a point-and-shoot camera, the sensor is only a few millimetres across, a two-thirds sensor (common on consumer-level dSLRs) is a lot bigger, although still smaller than the full-frame (35mm) sensor of professional dSLRs, and of course even that is a whole lot smaller than a medium-format digital back. (All of this feeds into why the highest quality photography, even in terms of film cameras) is often most associated with medium and large format.

Okay. So smaller aperture means a larger depth of field, but that means a bigger Airy disc, which means you need larger pixels (and the same number) to overcome the diffraction limit and get a sharper, better quality image.

Haynie has a Canon 60D, which he says has 4.3 micrometre pixels size. The Airy problem doesn’t arise at f/2.0, which such a camera. However, the pixels in older Smart Phone cameras are a lot smaller, perhaps 1 micrometre on a tiny sensor chip in order to cram as many as the market demands on such a small area. This means sharpness can be very limiting in older phones and many modern ones too. HTC and Apple have actually increased the size of the pixels on their sensors rather than increasing the megapixel count to overcome the Airy problem to some effect. Megapixel count always was marketing BS, anyway, because of all of the above and many other factors. Cheaper cameras (point and shot and/or phone) don’t have an aperture control or if they do it’s f/2 to a minimum aperture size of about f/4. You won’t be able to push it to f/8 or anywhere useful for depth of field. The size of the sensor and the pixels crammed in always mean passing the Airy border.

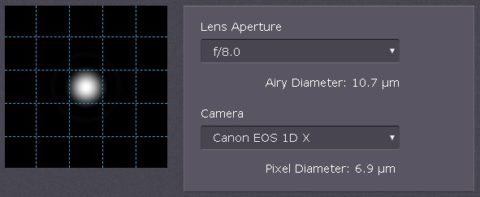

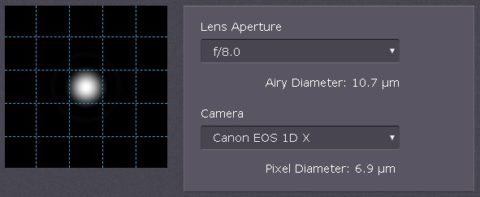

For that Canon 60D, stopping down to f/8 approaches the boundary as the Airy disc is about 10.7 micrometres at this aperture, stop to f/11 and it is 14.3 micrometres which is definitely larger than the width of 3 pixels on this camera. Contrast this with my Canon 6D, which has a full-frame (35mm) sensor. The pixels are a little over 6.5 micrometres and so I will be safe from Airy up to f/11. Take it to f/16 and it crosses the boundary. I reckon f/8 or f/9.5 would be the sweet spot for my moth macro setup. Assuming there’s sufficient light to keep the ISO low to avoid noise and the shutter speed short enough to avoid camera shake. I could use a tripod and remote shutter release with mirror lockup but that’s quite cumbersome when chasing small moving targets like moths. I do have the option of using Tamron’s onboard image stabilisation, which is worth two stops of shutter speed, so I can keep shutter long enough to let sufficient light in to avoid high ISO without introducing too much camera shake.

Your mileage will vary depending on what camera you are using. The Cambridge in Colour site has a more detailed explanation of Airy discs and a table to help you work out the optimal f-stop for your camera model. When you fill the form in it also simulates an Airy Pattern on your sensor, so you can see whether you’re at the limit with your camera for a given f-stop. f/8 is often considered a sweet spot, balancing reasonably large depth of field with minimal aberration due to Airy disc effect. The diagram below generated on the Cambridge site shows why this is the case.

Not to be confused with a second moth in the Noctuidae, the Hebrew Character, Orthosia gothica, that also bears a Hebrew nun on each forewing, although the two species are not particularly closely related despite appearances. It’s interesting to note (per Matthew Oates in his book In Pursuit of Butterflies) that The Setaceous Hebrew Character was the nickname of lepidopterist, entomologist, birdwatcher, and chemist Baron Charles de Worms (1904-1980), a balding and eccentric character of Austrian-Jewish heritage who worked at Porton Down and was a cancer specialist.

Not to be confused with a second moth in the Noctuidae, the Hebrew Character, Orthosia gothica, that also bears a Hebrew nun on each forewing, although the two species are not particularly closely related despite appearances. It’s interesting to note (per Matthew Oates in his book In Pursuit of Butterflies) that The Setaceous Hebrew Character was the nickname of lepidopterist, entomologist, birdwatcher, and chemist Baron Charles de Worms (1904-1980), a balding and eccentric character of Austrian-Jewish heritage who worked at Porton Down and was a cancer specialist.