TL:DR – How to fall in love with moths and mothing.

Regular Sciencebase readers will know only too well that back in July 2018 I got hooked on moths. An enthusiastic friend lent me a moth trap he had built himself for his children many years ago. The trap is basically a wooden box with a plastic funnel and an ultraviolet light supported by stiff plastic vanes).

The UV light attracts the night-flying creatures, some of them bump into the vanes, drop into the funnel and then find a cozy corner in one of the empty egg cartons put inside the box before “lighting up”. The amateur, or indeed professional, lepidopterist examines the catch at dawn, recording species and species number and later releasing the moths off-site back into undergrowth or bushes.

It’s fascinating and fun and at the time of writing almost five years since I first “lit up”, I have seen, photographed, and logged well over 450 different species of moth in my Cambridgeshire garden. The variety and diversity of shape, size, colouration, and patterning is incredible. I must admit that I had always been a little irrationally wary of moths despite the fact that they are completely harmless. After all, unlike many other types of insect, they don’t bite and they don’t sting.

It was a test run with my moth-trap maker friend, Rob, who had stopped trapping moth and turned his hand to making guitars, that got me hooked. He lit up one July evening and invited me to the grand opening the next morning. There must have been 100 or more moths in the trap, a few that were simply dull and grey or brown, but among them some huge hawk-moths, some shiny green moths, orange ones, red ones, patterned ones, ones with daggers and arches, all kinds.

Having got a little up close and personal with the Poplar Hawk-moth in Rob’s trap, allowing it to perch on my hand while I took a close look, this single dose of informal aversion therapy, seemed to cure my mild phobia about moths, my mottephobia. I had previously photographed one or two moths that turned up in the house, but essentially I made 180-degree about turn from aversion to addiction. I borrowed Rob’s trap from him permanently as summer turned to autumn, and paid him an honorarium for the privilege.

I have trapped regularly in all that time since. I’ve also acquired various other UV sources including a LepiLED. The low-wattage LepiLED runs off a USB battery pack and is entirely portable, so I have taken it on a few excursions with an adapted, portable Heath trap I bought off another ex-mothing friend. My pots for managing the morning moths came from yet another ex-mother friend!

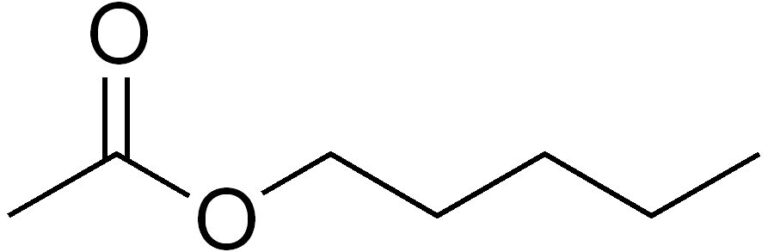

I have also bought pheromone lures to attract various species, including Emperor and some of the clearwing moths. I have planted wildflowers and various scented flowers in the garden to attract species like Hummingbird Hawk-moth and Convolvulus Hawk-moth. A recent addition to my mothing measures was to buy a bottle of amyl acetate (used in aromatherapy apparently despite it being toxic). It has a strong fruity smell and is entirely harmless to moths but attracts various species.

Is it a kind of madness, this mothematical obsession? Maybe. Am I happy to be part of #TeamMoth and to regularly declare that #MothsMatter? Too right! I have written about the ethics and importance of moth-trapping as a citizen science effort and I have also written about why moths really do matter. Would I recommend it as a hobby or citizen science project? By my scaly wings, I would, of course!

Incidentally, butterflies are just one grouping within the Lepidoptera, just like the less publicly familiar groupings, the noctuids, hawk-moths, erebids and others. Indeed, butterflies are grouping within the broader clade we know as the micro moths (an unfortunate term that doesn’t always reflect their size but is rather connected to their evolutionary ancestry). The other major clade is the macro moths, but there are some micros that are bigger than even the biggest macros.

The tragedy is that their numbers and diversity have declined considerably since my childhood in the 1960s and 70s. Perhaps even in the last five years since I started mothing. First full year, I would see a couple of hundred moths of 70 or so species, but in the last couple of years those numbers have been much lower even on peak summer nights.