Sodium benzoate (E211) is a public health issue that has been bubbling for fifteen years and could soon come to a head and have the fizzy drinks industry frothing at the mouth.

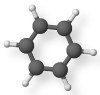

Sodium benzoate is a preservative added to carbonated beverages, but those drinks that also have added citric or ascorbic acid (vitamin C, E300) can be susceptible to the formation of benzene as a degradation product. At least that’s the theory.

The US Food & Drugs Administration (FDA) was aware of this issue in the 1990s and alerted manufacturers who were then meant to introduce a “quick fix” to prevent this carcinogenic degradant from forming in amounts above safety levels. However, there have been hundreds of new susceptible beverages brought to market the world over since by smaller manufacturers as well as the well-known ones and seemingly the benzene message has been lost in the intervening time.

Germany’s food watchdog, BfR, and the UK’s Food Standards Agency are currently testing drinks to see whether benzene levels are above WHO recommendations. Other countries are also on the alert. The renewed concern follows the FDA’s re-opening of an investigation, closed for 15 years, into benzene in soft drinks.

You can read more details of this at industry newsletter Beverage Daily

Some studies have shown that levels of benzene are present at five times the WHO’s limit for drinking water contamination and can occur in bottled soft drinks exposed to heat and light especially.

In acid conditions, benzoate is converted to benzoic acid (the active antimicrobial form, benzoate is added as a preservative for a reason after all) and it is thought that it interacts with hydroxyl radicals released by the ascorbic acid (better known as vitamin C) reaction with iron or copper ions in the water. These hydroxyl can decarboxylate benzoic acid, releasing carbon dioxide and leaving benzene behind. But, at what rates this occurs is not clear.

Moreover, leaving out the ascorbic or citric acid from soft drinks would be the simple solution and avoiding benzoate as a preservative in foods that contain these acids naturally would offer an end to the “problem”.

However, the issue brings to the fore once again the issue of acceptable risk. Sodium benzoate is present in soft drinks only in very small amounts and even if degradation were complete, the risk to someone drinking it is tiny. To have the same exposure as lab animals used to demonstrate carcinogenicity would mean a person having to drink 10,000 bottles of benzoate-containing soda.

Still, such minor details will not stop the media from jumping on this as the next big scare story despite the fact that it’s been around for years as public chemophobia.

UK paper the Times today picked up on the benzene in soft drinks problem I mentioned in sciencebase on February 22.

UK paper the Times today picked up on the benzene in soft drinks problem I mentioned in sciencebase on February 22.