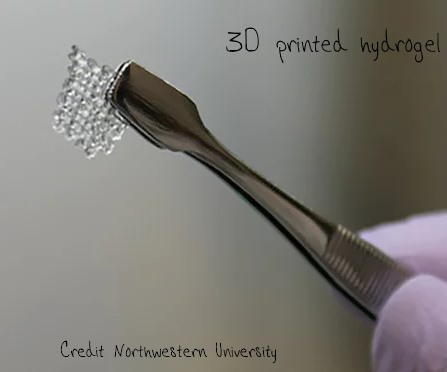

Scientists have used a 3D printer to make a scaffold of a soft plastic type material known as a hydrogel. The researchers then loaded this scaffold with the egg sacs known as ovarian follicles from a female mouse and implanted it. The follicles began maturing and released eggs, which were fertilised by natural mating and the mice then went on to give birth to live young. [Laronda et al, Nature Commun, 2017, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15261].

A similar synthetic ovary might one day be used to treat infertility in women who have had cancer chemotherapy. Chemotherapy causes ovarian failure, essentially destroying a woman’s eggs of which they have a limited supply. Men, of course make sperm all their lives, but women are born with all the eggs they will ever have in immature form in their ovaries. Chemotherapy at any point in their lives will destroy their eggs, some women and girls choose to have eggs harvested and cryogenically stored before they start treatment to improve their chances of an IVF baby later in life.

The picture is quite complicated concerning what the anticancer drugs actually do to the ovary. Quoting from this research paper:

“[Premature ovarian failure and thus female infertility] results from the loss of primordial follicles but this is not necessarily a direct effect of the chemotherapeutic agents. Instead, the disappearance of primordial follicles could be due to an increased rate of growth initiation to replace damaged developing follicles.”

The current research itself is all about testing egg follicle survival and showing how they can be viable on the porous scaffold of the synthetic ovary. Moreover, the team has shown that follicles on the scaffold release appropriate hormones as they would in a living ovary and release maturing egg cells. It all looks very promising for mice. Human follicles grow much larger than mouse follicles and would bring different challenges in terms of keeping them alive in an artificial ovary, but this is a step closer.

The obvious question though is what was the source of the implanted follicles. The team describes how “follicles were mechanically isolated” from an excised mouse ovary for implantation. But, if a women has premature ovarian failure induced by chemotherapy, then there are presumably no follicles with which the fertility team could work unless they have been “harvested” prior to her treatment, which would be an additional (surgical) procedure the patient would have to face and a difficult choice made regardless of whether the patient is a baby, small child, teenager or adult.

![151026-Tobacco-vs-Meat-TWITTER[1]](https://www.sciencebase.com/images/151026-Tobacco-vs-Meat-TWITTER1.png)