Photography, as with any other visual art form, hinges on a blend of technical skill and creative vision. While perfection can be elusive and subjective, achieving a “half-decent” photo that captures attention and tells a story is almost always an attainable goal whatever your skill level and with whatever equipment you have. Remember, if you want a photo, any camera is better than no camera (we’ve all been there and done that!). Meanwhile, here are a few thoughts on how to lift the passable snapshot to the inspiring image.

You can take a look at some of my photographic work and decide whether I live up to my own standards here.

Understanding light – Light is the fundamental of photography. Whether you’re working with natural or artificial light, how you harness it can define your photo. For instance, the magical Golden Hour: Early morning just before sunrise and late afternoon just before sunset offer soft, warm light that flatters most subjects. Shadows are gentle, and the light’s directionality adds depth.

Contrast that with the serenity of Blue Hour: The moments before sunrise and those after sunset provide cool, moody tones ideal for atmospheric shots. It’s also worth adding that darkness and shadows are not the enemy of the photographer, indeed they help you create drama, texture, and contrast. Timing the shadows in a landscape or even a portrait lets you leap from flat to dynamic.

Correct exposure – A well-exposed photograph is the foundation of visual appeal. Proper exposure ensures that details in both highlights and shadows are visible without appearing bleached out or overly dark. While modern editing tools allow some latitude for correcting exposure, it’s always best to get it right in-camera. Understanding your camera’s metering modes and how they interact with the scene’s light levels is the key. Also, shoot in RAW every time if that’s an option it then gives you the chance to retrieve detail from seemingly over-exposed or under-exposed areas in your photo and balance once against the other.

Sharp focus – A blurry subject can ruin an otherwise excellent composition. Ensuring your subject is in sharp focus is non-negotiable, unless the blur is the artistic choice. Autofocus systems have become highly advanced, but their capabilities must be matched with a keen eye for detail. For portraits, focus on the eyes. For landscapes, ensure the desired depth of field is achieved. The sharpness guides the viewer’s attention to what you want them to see. Of course, depth-of-field is like any commodity. You may want a short depth of field for a portrait so that the background is blurred, but for a macro shot you may want the whole frame to be sharp. This comes at the cost of how much light reaches your sensor or film. Smaller aperture means less light getting in, but a bigger depth of field.

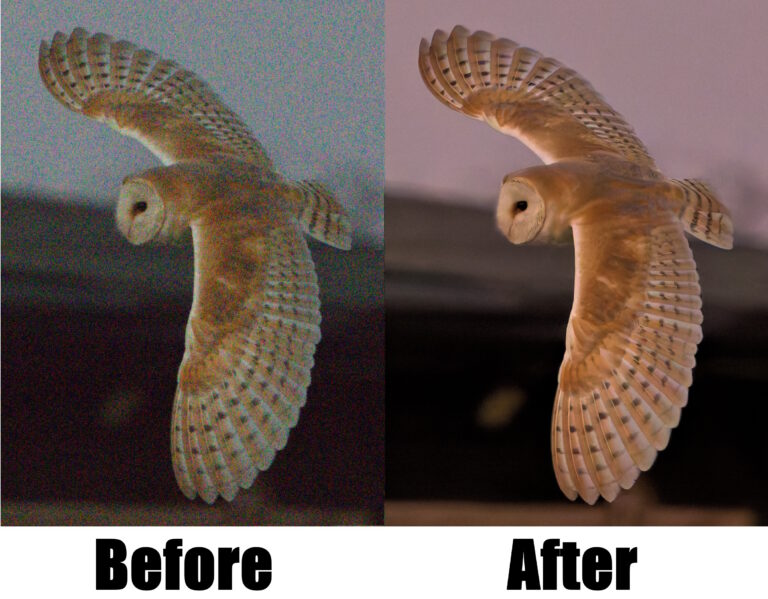

De-noising grainy images – Noise, especially in low-light conditions or at high ISO settings, can detract from a photo’s quality. While some genres, such as street photography or film emulation, embrace a certain level of grain for artistic purposes, overly noisy images in genres like wildlife or portraiture can feel distracting. Post-processing can sometimes help you clawback the clarity, working best with RAW files.

Artistic cropping – Cropping is a powerful tool that allows photographers to refine their composition post-capture. A thoughtful crop can eliminate distractions, emphasize the subject, and create visual harmony. Whether filling the frame with an intimate close-up or leaving negative space or background for context, the crop should complement the story you’re telling. Remember the rule of thirds but don’t be afraid to break it if the composition feels stronger with different angles and different space.

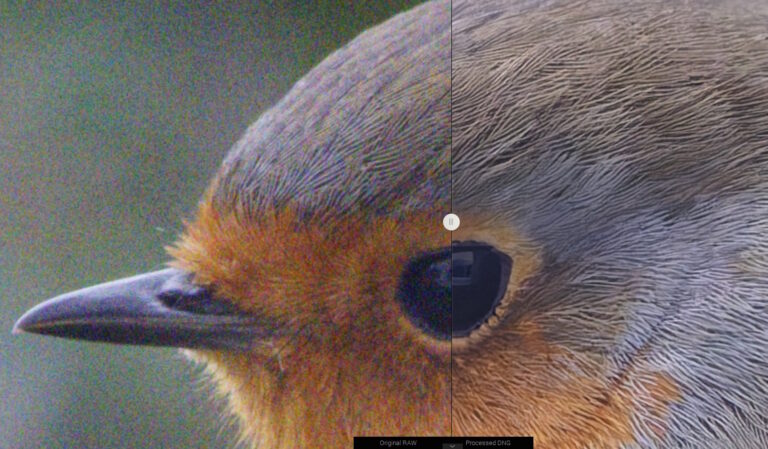

Animal photography: The leading eye – When photographing animals, the leading eye must be pin-sharp. This draws the viewer’s attention and conveys emotion and personality. The leading eye acts as a visual anchor, guiding the viewer through the frame. Shots where the animal is looking away don’t often work, unless the context justifies it. For example, a distant gaze that matches a dramatic landscape or tells a broader story about the animal’s environment.

Catchlights: Breathing life into eyes – Catchlights, the reflections of light in a subject’s eyes, add depth and vitality, particularly in animal or human portraits. Without catchlights, eyes can appear flat and lifeless. Photographers often use natural light or controlled artificial light to introduce this subtle yet critical element. Catchlights don’t just reveal the light source; they transform the image by infusing character and emotion.

Photography, like any art, is about emotion. You need patience to get that perfect light, expression, or moment, but that patience can be rewarded with the shot you’re really after rather than the record shot you’d quickly snap just to make do.

Learn the rules so you can use them to best effect when they’re needed, but also so you can break those same rules when it means a better photo. You can ditch the rule of thirds, the golden ratio, you can try unusual angles or play with unconventional perspectives. Focus on that unusual aspect of the subject, not the obvious. Observe and try to see things from a different angle to help you tell a unique story with your photos.