Recently, there have been several Marsh Harriers (Circus aeruginosus) over the reedbed trail at RSPB Ouse Fen, reached from Needingworth in Cambridgeshire. It’s a little over 4 km from the Needingworth reserve car park to the far reaches of this trail but you do get to walk through the main RSPB reserve, which I’ve mentioned before and cross the Great River Ouse at a sluice bridge. I was lucky enough to see some of them, male and female, on a visit to the reserve in early May 2018. Also showing well were several warblers (Sedge Warbler, Whitethroat, Lesser Whitethroat), Common Tern (Sterna hirundo), Hobby (Falco subbuteo) hunting dragonflies and other airborne insects, a distant courting pair of Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus), a couple of Kestrels (Falco tinnunculus), Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus).

Pictured above is a male Marsh Harrier hunting over cow parsley at the far end of the reedbed trail. The water tower in the background of the shot is near the village of Over, I believe, although I cannot quite pinpoint it on the map.

Below is a Hobby one of several over the reserve, hunting dragonflies, the bird having migrated from its wintering in warmer climes. It’s relatively easy to photograph them as they reel around the vast fenland skies but as soon as they stoop on their prey they accelerate quickly, so feel quite privileged to have caught this one just as it’s about to grab its lunch.

Common Tern, one of a pair, although there were a few more around, hovering over one of the reed-lined waterways.

A pair of Cuckoos cavorting in the distance. I estimate I was about 500 metres away from them, but could clearly hear their call and got several more shots with a 600mm zoom. If you look closely, you can just see a male Reed Bunting (Emberiza schoeniclus) perched to the left of the pair. As far as I know, Cuckoos prefer warbler nests and presumably, the Reed Bunting’s eggs are safe from these brood parasites.

There have been several sightings of Cranes over the last few months, we’ve seen them at WWT Welney, RSPB Lakenheath, and RSPB Nene Washes, and now one, overhead, at Ouse Fen.

Pictured below is a female Marsh Harrier with identification tags on its wings. I contacted David at RSPB Lakenheath (he runs the Twitter account RSPBFens to find out more about the specimen.

“The RSPB have been wing tagging harriers but other organisations have also been tagging them,” he told me. “According to Simon, our local bird ringer, this bird was ringed (6A) west of Norwich as a female chick in June 2017.” It was seen locally throughout August to October and then seen on 7th January 2018 at Salceda Marshes, near Guarda, Pontevedra, Spain. It has been back and forth between Norfolk and Spain ever since, last update was for October 2021, Ilha da Xunqueira in Ponetevedra.

There were also some waterfowl but not many in this part of the reserve (Coot (2-3), Mallard (a couple of pairs), Tufted Duck (small flock, 7-8), Great Crested Grebe (one pair), Mute Swan (2 or 3), Pochard (1), Greylag Geese (two flocks of a dozen or so), Lesser Black-backed Gull, Black-headed Gull). Also, heard but not seen Yaffle (Green Woodpecker), Reed Warbler, Grasshopper Warbler, booming Bitterns.

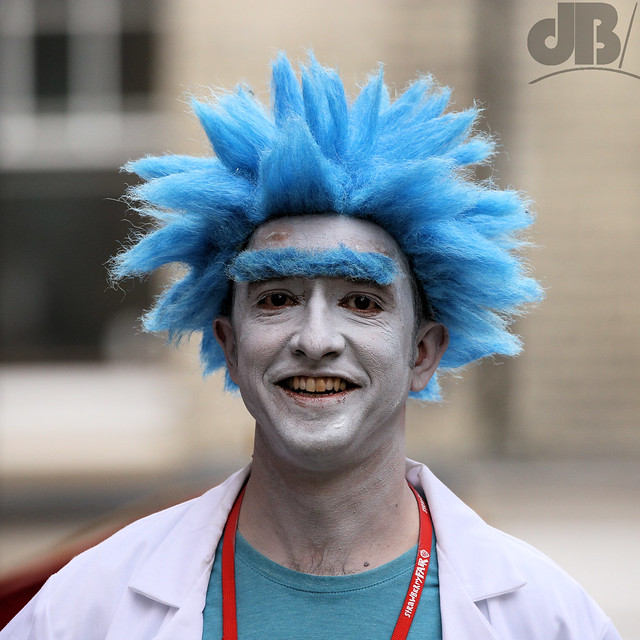

Breaker, breaker, do ya copy?

Breaker, breaker, do ya copy?

Groyne injury

Groyne injury

As well as the Reed Bunts, Linnets, and Whitethroats, mentioned earlier, there are also lots of Yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella) and Corn Bunting (E. calandra) around the Cottenham Fen Edge at the moment.

As well as the Reed Bunts, Linnets, and Whitethroats, mentioned earlier, there are also lots of Yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella) and Corn Bunting (E. calandra) around the Cottenham Fen Edge at the moment. A couple of Corn Buntings perched on overhead wires allowed me to get fairly close to photograph them before flying off into the wheat fields.

A couple of Corn Buntings perched on overhead wires allowed me to get fairly close to photograph them before flying off into the wheat fields.

Flying Free

Flying Free