TL:DR – Recent research has demonstrated that adding the volatile organic compound amyl acetate to a scientific moth-trap can boost the number of moths attracted to the UV light by almost a third.

A social media discussion about UV light sources for scientific moth-trapping, the type of vanes on the trap, and the environment in which one traps brought up some interesting thoughts. Several moth-ers use double sources to give them a better chance of enticing numbers and diversity to their traps. Although moths have been shown almost always to simply opt for the most energetic (higher frequency, shorter wavelength) when given a choice. There is evidence that black lights (UV bulbs painted black) are not so effective for attracting those species that are drawn more to visible light.

Also, it seems that white plastic vanes seem to work better than other types of vane and certainly better than rain-shield supporting rods on the commonly used Robinson and Heath moth traps. It also seems that the specific terrain and vegetation can affect numbers and diversity in some ways more than light source or other factors. There was also some recent work on how low-wattage UV light sources have a very limited range of attraction, but also the range varies among macro moth families, some attracted from 30 metres others from just 10 metres.

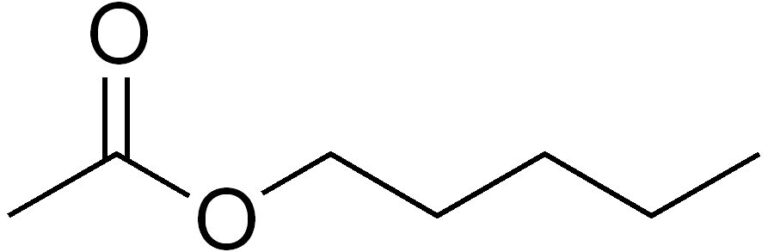

Anyway, in the discussion, fellow moth-er Stephen Roughley mentioned a paper by Chris Tyler-Smith and Yali Xue in the journal Ent Rec, “Amyl acetate increases macromoth catches in light traps” 2021, 134(6), 315-321, that looked at how lepidopterists might boost their haul for scientific and citizen scientific purposes. They suggest the use of a simple organic molecule that smells of fruit, called amyl acetate, amyl is an alternative name for the five-carbon alkyl chemical group pentyl, to augment one’s trapping. They demonstrated that amyl acetate boosted the number of macro moths drawn to the UV trap by up to about a third. Strictly speaking, the product contains 3-methylbutyl acetate, so five-carbon group but not in a straight chain.

The molecule, sometimes known as pear oil, is used as a flavouring agent, as a paint solvent, and in the preparation of penicillin. It is also the fuel for Hefner lamps. But, it is also found naturally in the volatile organic compounds exuded by ripe pears and presumably other fruit and fermenting or decaying vegetable matter.

I asked author Xue about the work. “We only tried amyl acetate from Etsy, but suspect that moths would not care about the grade, and any that smells like pear drops to a human would be fine, they told me. “We used enough to moisten a cotton wool pad and placed this beside the trap in a metal bowl as the solvent dissolves plastics.”

Many species of moths are known to be attracted to the odours given off by ripe fruits and flowers. There is a suggestion that some female moths may well be particularly attracted to such odours, including amyl acetate, as they seek out ripe fruit in which to lay their eggs. Indeed, it’s worth noting that a lot of moths that are not necessarily interested in light can be drawn to a strong-smelling sugary solution made from molasses boiled with beer or wine and various other concoctions. Most moths use their olfactory senses to locate food, mates, and suitable habitats, so this is perhaps not surprising. It was the technique of sugaring to attract moths that inspired the team. (See also wine roping). Amyl acetate mimics fruit odours and so should attract moths. Indeed it has been used in the past as a sugaring ingredient.

The team suggest, however, that the chemical simply applied could substitute for sugaring concoctions and might boost moth trapping where scented flowers are not present at a site. It all adds to the useful data that might be gathered to feed back to moth recorders for scientific purposes and to show where and when various species appear around the country. I have previously discussed the pros and cons of moth-trapping on Sciencebase.