This is a male of the moth species Nemophora metallica. I’ve written about them on the blog several times over the last couple of years.

Those “horns” are the male’s antennae. They can be up to three times as long as the moth’s forewings. The female’s antennae are half the length. The species loves a bit of Field Scabious (Knautia arvensis) it being the larval foodplant. The dayflying Brassy Longhorn is found in the South of England and across East Anglia generally where Field Scabious grows. They are on the wing in June and July.

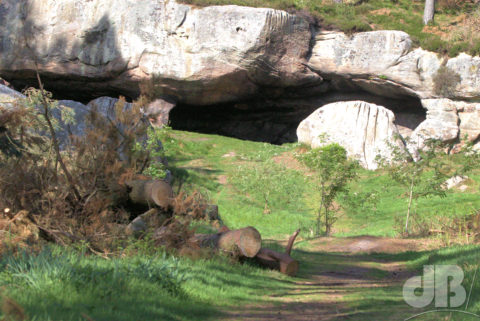

Thankfully, last year I managed to persuade the Environment Agency not to prematurely mow the patch along the Cottenham Lode where this species seemed to be thriving these past couple of summers. I hope the EA sticks to its promise again this year, so these little beasties have a better chance of reproducing and the scabious of setting seed. The next step is to persuade the EA to halt all spring/summer mowing of the banks of the lodes so that other invertebrate and botanical species might get more than a foothold. Obviously, the Agency has to consider water flow as the lodes are drainage ditches that criss-cross the Fens. That said, there is no obvious need to remove vegetation so brutally as they often do in the spring/summer if at all.