Back in September, the number of starlings on farmland around the village seemed to build. It seemed early for the European winter influx, maybe it was just wishful thinking. I was hoping for large numbers that would begin to murmurate over the Broad Lane balancing pond before diving into their nocturnal roost in the reed bed there. (This particular video of mine was from November 2018)

Other concerns took over my thought processes, as they are, in October and early November, and I’d all but forgotten about the starlings by the time the local birders started pinging me about rising numbers 30 to 20 minutes before sunset over the pond. When I finally got the opportunity to check out the swooping and swirling of these maestros of social distancing, the murmurations were occurring most evenings and the numbers, I and birding friend Neil (watching at two-metres distance) estimated there were about 6000 there. Quite an amazing sight and the whooshing as they soar close overhead before diving into the reeds is astonishing. The next evening, the numbers had grown, perhaps to around 7000.

That was the peak for Cottenham’s murmuration. Over subsequent nights and having shared video on social media and mentioned to a few friends, the numbers began to decline as the number of observers rose. At the human peak, I think there were about 20 people, adults and children and a few pet dogs, waiting patiently for Dave’s Spectacular. It hadn’t happened in Cottenham again as far as I know. Another friend, Liz, reported that their daughter suggested 12 starlings wasn’t quite what you’d expect from Sir David…

Meanwhile, the Cottenham birder list alerted me to a large number at RSPB Fen Drayton, some 7000 birds were murmurating there over Elney Lake. It could easily be the same flock that apparently had departed Cottenham. There was also a peregrine falcon there hunting through the flock. Indeed, murmurating is flocking behaviour to reduce the risk to the individual bird being predated by such raptors ahead of bedding down for the night. I got a little distant video footage of those birds.

Also to be seen at Fen Drayton, four cattle egrets, birds that until recently were rarely seen in the British Isles, but whose numbers like those of the Little Egret and Great White Egret, ostensibly “foreign” birds have been growing over the last couple of decades. Climate change may well be playing a part in how such species are extending their range.

The story doesn’t end there. We visited RSPB Ouse Fen (Reedbed Trail side, accesses from the car park at the Over edge) one morning in mid-November. The RSPB warden – Hannah Bernie – was still there with her team hacking back reeds with a view to increasing plant, and thence animal, diversity on the reserve. She told us that they had spotted another rare visitor, a glossy ibis. The bird had been spotted at Fen Drayton a couple of nights before, but had flown, and this was presumably the same bed making Ouse Fen its temporary home. One birder I spoke to on the day I saw the GI told me he’d seen five or six on the reserve during the last decade or so.

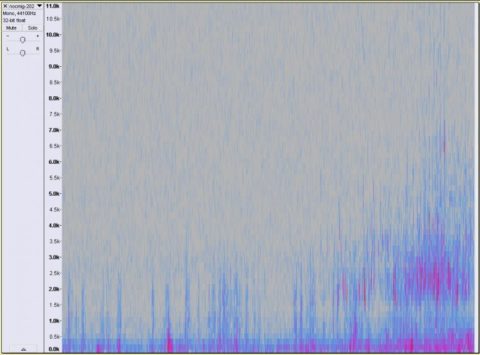

The warden also mentioned in passing that they had a large starling murmuration of about 10000 birds. I felt obliged to return that evening to witness the spectacle. That night I would estimate that there were at least twice as many birds as there had been at Cottenham’s peak, so perhaps 14000.

Of course, such numbers are minuscule compared to other murmurations such as the knot (a wader, or shorebird) that one sees at this time of year, hopping the tide at RSPB Snettisham in North Norfolk. We saw 68000 of those birds there in September and the numbers had doubled by late October. And those numbers are dwarfed by the multi-million strong murmurations one might see in the original sub-Saharan homes of some of those “foreign” birds I mentioned. Where vast, entrancing murmurations swoop and swirl above the cattle egrets pecking at the feet of herds of majestic wildebeest. Still, we must enjoy the nature to which we have relatively easy access, especially in times of covid.

Sir David Attenbradley

The Wormwood

The Wormwood