I had a discussion recently with a former moth-er who disposed of her trap after having an ethical pang of conscience about all the moths she had been disturbing over the years. She suggested that there are hundreds of thousands of people trapping all over the country and that we’re interfering with reproduction cycles by doing so. I felt her opinion was at best misguided.

My immediate thought was that that number was way off. I know two other people in this village of 4000 or so who trap regularly, as do I, but this is quite a sciencey village, close to Cambridge, so could be exceptional. There’d have to be 3-4 people in every of the 44000 villages and towns across the UK for there to be hundreds of thousands of people trapping. This from a straw poll I conducted among moth-ers online is very unlikely. If anything there are a few hundred across the British Isles mothing regularly, maybe at most 1000. Even if we assumed 1 per 1000 households, there are just 28 million households, that would still only be 28000, but I reckon the hobby is done by far fewer people.

Either way, is “catch-then-release” moth trapping detrimental to moths or does the scientific knowledge that might be gleaned and the raised environmental awareness among those who moth outweigh any negative effects? Perhaps we could consider the impact of mothing in the context of the hundreds of moths consumed by a single bat eat each night. My trap usually has a few dozen moths by morning. I’ve seen three Pipistrelle bats circling our garden together at dusk, over the years, long before I was mothing. Through the night they will be hoovering up a lot more than any single trap catches.

I think the real problem isn’t those interested in the insects. It’s widescale habitat destruction, intensive farming, and climate change, these are having a much bigger detrimental effect on moths. Moreover, moth trapping is about respect for nature, moth awareness and understanding, and record keeping add to our knowledge about the rarities, their behaviour, their behaviour, migration, and range extension trends. If moth-ers submit records and share information, and discuss their mothing, which a lot of them do, that can only be a good thing for lepidoptery. It might even guide those who try to look after the environment, and perhaps even nudge development away from sensitive areas.

I asked members of the UK Moths Flying Tonight Facebook Group for their thoughts on this subject and reproduce a few of their comments, edited for brevity here:

Martin H: I trap once or twice a month on my local patch. However, I’m involved in a project to monitor the moths of the Balearic Islands and will trap every night in the same place for anything between one and six weeks. There is absolutely no evidence that this has any adverse effects on numbers or species diversity and the project itself has been going for more than 25 years. There’s also no evidence of recapture of the same individuals. Local habitat change has had an effect. This is all based on my experience as a professional lepidopterist for 40 years.

Gary G: I’m not a moth trapper, I joined to learn more about moths. From my experience collecting ladybirds using sweep nets and beating trays I often find they mate in my specimen tubes before I release them. I wonder if this happens in moth traps?

Alan S: Yes it does. Sounds like [mating in moths traps] might be a beneficial side effect then. Add to that the huge benefits gained for ecology from recording the moth distribution and population trends and I’d say you’re on to a winner.

Jerry S: Also, more male species seem to be attracted to light.

Alan S: In the grand scheme of things it doesn’t make much difference unless people are constantly trapping the honeypot sites for scarce species and even then as long as it’s catch and release it should be OK. We survey lots of sites and these don’t get done as regularly as we’d like. The sites are huge and we only cover a tiny fraction each time we survey so impact is negligible.

Shaun P: If trappers are doing the right thing and sending in records, it should be easy to find out the number. I’m in Cornwall and I suspect the number of regulars is quite low judging by records and talking to others.

Sean O: Cars are a bigger problem…a drive in the countryside at night, moths continually in the headlights with several hitting, then multiply that by the number of cars on the roads around the country…that’s a lot of moths in a year!

Giles K-S: My experience (in rural Herefordshire) is that I actually see very few moths in the headlights – so few that you can almost count them individually. I think it’s just a symptom of the wider decline in insect numbers.

Mark G: I hardly see any. I remember the moth snowstorms of old in the 1960s.

Sciencebase: Yes, been discussing this for a while, 15-20 years ago, driving anywhere meant cleaning the windscreen regularly, not so these days.

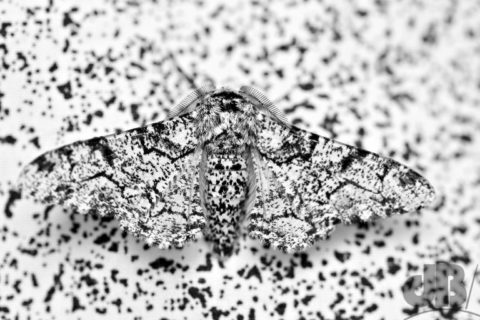

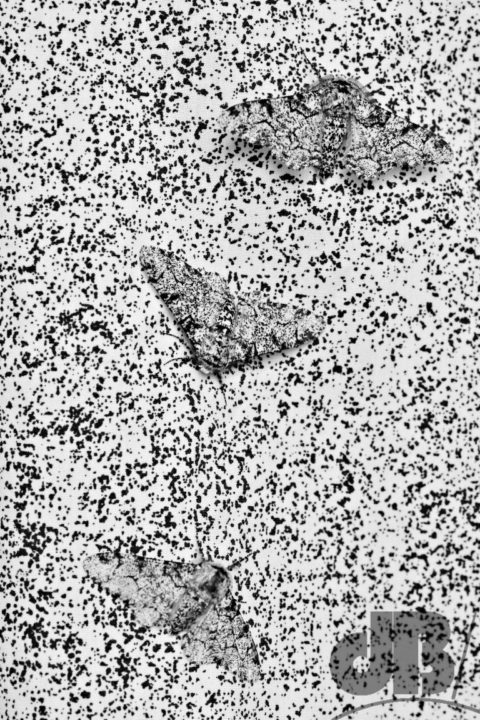

Giles K-S: Moth traps only attract moths passing within a very short distance of the trap – in the range of 3 to 10 metres. Of much greater concern is the large number of other artificial light sources disrupting the activity of moths, bats and other nocturnal species.

Mark S: There are certainly [fewer] than 150 trappers in VC55 Leics & Rutland, and I’m sure there are many VCs with many fewer. Responsible catch & release, and recording does far more good than damage.

Leonard C: Static traps run all the time all around the country and provide valuable data. The only way we can help decline is to actually record numbers and then act upon such data by increasing habitat and foodplants.

Summer de G: [Moth-trapping] probably has no more impact than leaving outside lights on all night or garden lights.

Ben S: Moths are at more danger from birds, the bat roost at the bottom of my garden, artificial lights at night, and our clearing land, driving our cars etc.

Derek C: [Simply] mowing the lawn probably [kills] quite a few!

Kiera C: I think moth people are likely to be far less of a problem than the broadcast application of pesticides by industrial agriculture, the destruction of habitat, and the effects of climate change. If trapping and freeing moths just gets people to think about those bigger issues, to join environmental groups, to change their patterns of consumption, and to see the beauty in nature so that they want to look after it and protect it, then that possibly outweighs harms.

Lee T-W: I find that numbers in my garden increase slightly year on year (for common species). I wonder if attracting them brings them together to create greater breeding opportunities, also trappers are likely to manage their mini-habitat more beneficially?

Pete M: As long as people are sensible with holding off if you’re attracting predators, do all you can to prevent casualties, don’t trap every single night, and always send records in so your data has some use, I can’t see any real ethical issues.