I’ve put together a menu of my favourite food myths #DeceivedWisdom and separated the fact and fiction based on the debunking of nutrition myths in a recent well-referenced feature on examine.com. Myth 10 is my own bonus myth debunked.

Myth 1: Carbs are bad for you

Fact: As long as you do not overindulge, there is nothing inherently harmful about carbohydrates.

Myth 2: Fat is bad for you

Fact: If you eat too much and don’t get enough exercise, and so stay in a caloric surplus, a low-fat diet won’t help you lose weight. You need some omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Saturated fat won’t give you a heart attack, but too much trans fat might.

Myth 3: Protein is bad for your bones and kidneys

Fact: Protein, even in large amounts, isn’t harmful to your bones or kidneys (unless you suffer from a pre-existing condition).

Myth 4: Red meat is bad for you

Fact: The risk of getting cancer from eating red meat has been vastly exaggerated. Healthy lifestyle choices, such as maintaining a healthy weight, exercising, not smoking, and drinking alcohol only in moderation is far more important to overall risk.

Myth 5: Salt is bad for you

Fact: Salt reduction is important for people with salt-sensitive hypertension, and excess salt intake is associated with harm. But drastically lowering salt intake has not shown uniform benefit in clinical trials. See Myth 4 for general comment on health risk reduction.

Myth 6: Fresh is better than frozen

Fact: There are only tiny nutrient differences between truly fresh fruit and veg compared with frozen produce. Choose to suit your taste, budget, and lifestyle, any fruit and veg is better than no fruit and veg. Some supermarkets cold store “fresh” fruit and veg for months, so in that case frozen might even be fresher.

Myth 7: You should do a ‘detox’ regularly

Fact: The concept of a detox is pseudoscience. Nothing dietary you ingest will accelerate significantly the body’s natural processes (in the liver and kidneys) of waste products. Moreover, some supplements add to the burden on the liver and can even interfere with medication, leading to more tox than detox.

Myth 8: Breakfast is the most important meal of the day

Fact: You don’t need to eat breakfast to be healthy or lose weight.

Myth 9: You won’t lose weight if you eat before bedtime

Fact: Eating late won’t make you gain fat, unless it drives you to eat more. Also, tasty, high-calorie snacks are very attractive after a long day.

Myth 10: There is a magic formula to make you healthy, wealthy, and wise

Fact: There isn’t. Eat sensibly, don’t overindulge in any one food, get plenty of exercise, preferably in the fresh air where you can hear birdsong away from traffic. Don’t smoke. Don’t drink to excess. Avoid worrying about your health and nutrition.

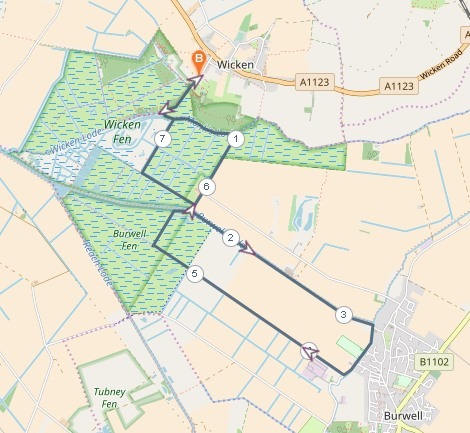

Like I say, there were quite a few people on the Fen watching out for owls and hoping for a great photo.

Like I say, there were quite a few people on the Fen watching out for owls and hoping for a great photo.