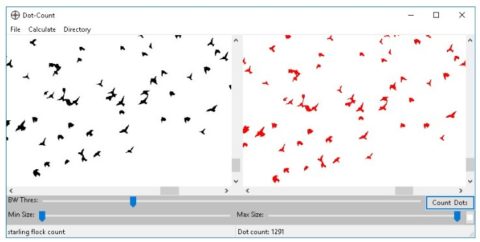

Watching the Starlings murmurate over Broad Lane balancing pond, I estimated that there were 3-4 large flocks of about 1000 birds each and then maybe a dozen smaller flocks of 50-100. But, then I found an interesting image analysis tool called Dot-Count into which you feed a photo with objects you wish to count that you have made monochrome and boosted the contrast. I used a cropped version of the above photo:

You set a threshold for the smallest object and the largest object (dot) and a threshold for contrast and ask it to “Count Dots”. It reckons there were 1291 “dots” in this image, but a quick look showed it had missed a few overlapping birds. So, let’s just guesstimate there are 1300, so my 1000 guess wasn’t too far off.

Three or four similarly sized flocks were wheeling around the sky at the time as well as those smaller ones. I reckon the Broad Lane reedbed roost is host to a staggering 4000-5000 Starlings each night.

Interestingly, the Dot-Count page at the Reuter Laboratory at MIT, uses Starlings as one of its examples. The first photo they show has roughly the density of my flock and a count of 800, so same ballpark figure. They reckon you can count lots of other types of object in a photo as long as they’re non-contiguous and you can increase the contrast sufficiently to allow the software to do its job: windows on a skyscraper, eggs in a basket, nanoparticles and neurons, freckles on a face etc. Presumably, you could even use it for counting crows…

In case you missed it, you can watch my documentary about the Cottenham Murmurations narrated by Sir David Attenbradley here.

UPDATE: March 2024 – My estimates of the various and vast Starling murmurations at RSPB Ouse Fen (Earith) would suggest there were around 500-750k birds!