Across the globe privacy laws and property rights are confused. Having usually been established in centuries past it is unlikely that any established legal system can cope easily with the requirements of the digital age. Nowhere is this more likely to hold true than when discussing the use of peoples’ biometric information, which are very personal data indeed.

Across the globe privacy laws and property rights are confused. Having usually been established in centuries past it is unlikely that any established legal system can cope easily with the requirements of the digital age. Nowhere is this more likely to hold true than when discussing the use of peoples’ biometric information, which are very personal data indeed.

Biometric information might include iris or retinal scans, digitized fingerprints, DNA samples, even lip-recognition knee X-rays, or any of dozens of other measurements and readings that could be collected from an individual and that would be unique to that person.

Yue Liu of the Norwegian Research Center for Computers and Law, in Oslo, suggests that there is a legal precedent for treating biometric information as personal property rather than data acquired. She adds that the viability of her argument should apply equally well to the legal systems of both the United States and the European Union.

Some observers have previously argued that because current legal systems are inadequate in protecting society from data misuse that ascribing property rights to digital information might allow its regulation and protection. Others have argued that these so-called inadequacies do not exist and that present legal frameworks are perfectly able to cope with the digital age without the addition of yet another layer of regulation.

I asked Liu what aspect of the term property she was concerned with. “My paper about property right and biometric information, doesn’t refer to ‘intellectual property, I was only talking about it as a ‘personal property’,” she told me, “Because biometric information is some kind of bodily information , I don’t think it is very accurate to regard it as an intellectual property, but I think it may make sense to regard it as a property of an individual since it is so intimately linked with our body.”

To my mind, however, I think Liu is missing a trick. I think biometric information is more akin to intellectual property (data gathered about a person’s blood type, fingerprints, iris pattern) than property in the old-school sense of something we own like our clothes, a car or a homes.

If someone steals the shirt of your back, then you no longer have that piece of apparel, that is conventional theft. Whereas someone manufacturing an unlicensed generic version of a patented invention has stolen the intellectual property but not the physical property of an individual example of that invention. If someone steals your biometric data, then surely that is more akin to the latter example than taking a piece of clothing.

I get the feeling that Liu’s paper argues the idea into a corner. Would a judge equate biometric information with a physical possession? I suspect that they are more likely to equate biometrics to other forms of data and IP rather than possessions.

Liu argues that neither side of the debate is without controversy. No law is wholly capable of coping with all situations but in the context of biometric information a property-rights based law might operate to protect the individual, their biometric data, and prevent misuse.

“Strictly speaking there was not yet any precedent that treat biometric information as personal property,” she concedes, “The precedent I mentioned was just something that might be compared to or is related to biometric

information.” Genetic information, human tissues, voice recordings,

and pictures, all might be considered as related in this way. “I attempted to find some legal basis that might be used for treating biometric information as personal property, and I found it possible both in the United States and EU legal system,” Liu asserts.

We are increasingly using online social media, digitized medical records, and plastic money and store loyalty cards. It is becoming obvious that information generated by our transactions with websites, sellers, banks, healthcare workers, and others is being transformed into a commodity to be sold by the information industries. There are obvious benefits for that industry to gathering and marketing such information. However, privacy remains a controversial aspect of any such transaction even in the case of medical data where the data might have long-term social benefits through improvements in healthcare that result from its analysis.

Biometric information is a special category of personal information. It is usually a unique representation of a person’s identity and is, by definition, intimately linked to that person’s body.

“Does that indicate that in the context of biometrics, the argument about using property rights as a protection measure for personal information will find more legal justification?” asks Liu.

Given that our personal data is becoming increasingly marketable, it may be beneficial to recognize a property right in relation to the commercial exploitation of our biometric data, asserts Liu. “Such data, being intimately linked to individuals and helping to make them special and unique, ought arguably to belong to the individual from whom they are ultimately derived,” she says.

The liberal discourse on property rights during the nineteenth century focused on individual freedoms and rights and led us through enormous changes of the industrial age and throughout the twentieth century. If the twenty-first century is the digital age, then perhaps it is time to begin a new discourse regarding our individual rights and freedoms regarding the use of our very personal data.

![]() Yue Liu (2009). Property rights for biometric information — a protection measure? International Journal of Private Law, 2 (3), 244-259

Yue Liu (2009). Property rights for biometric information — a protection measure? International Journal of Private Law, 2 (3), 244-259

Batteries are included (unfortunately) – A chemical cocktail of toxic gases is released when you burn alkaline batteries, according to the latest research from Spain. The investigating team highlights the issue with respect to municipal waste incineration, which is used as an alternative to landfill and suggests that recycling is perhaps the only environmentally viable alternative.

Batteries are included (unfortunately) – A chemical cocktail of toxic gases is released when you burn alkaline batteries, according to the latest research from Spain. The investigating team highlights the issue with respect to municipal waste incineration, which is used as an alternative to landfill and suggests that recycling is perhaps the only environmentally viable alternative. Dioxins Before Swine – Irish pork is off the menu, according to the BBC.

Dioxins Before Swine – Irish pork is off the menu, according to the BBC. If you ever thought genetics was only about disease, then check out the popular SNPs list on

If you ever thought genetics was only about disease, then check out the popular SNPs list on  Thousands of babies had apparently taken ill having drunk

Thousands of babies had apparently taken ill having drunk  Before reading on, and specifically before asking why I’ve used a picture of Buddha in an article about Ayurveda…it’s not Buddha, it’s Nagarjuna, redactor of the Sushruta Samhita a sixth century BCE text on surgery, the only treatise for two of the eight branches of Ayurveda. The snake is part of Nagarjuna and is usually depicted as a protective canopy, I’ve never seen Buddha depicted in that way. Apologies for any confusion, but please no more comments or emails telling me I’ve used an inappropriate photo. I don’t believe I have.

Before reading on, and specifically before asking why I’ve used a picture of Buddha in an article about Ayurveda…it’s not Buddha, it’s Nagarjuna, redactor of the Sushruta Samhita a sixth century BCE text on surgery, the only treatise for two of the eight branches of Ayurveda. The snake is part of Nagarjuna and is usually depicted as a protective canopy, I’ve never seen Buddha depicted in that way. Apologies for any confusion, but please no more comments or emails telling me I’ve used an inappropriate photo. I don’t believe I have.

I don’t know anyone who hasn’t got a cancer story to tell, whether it is personal experience, a relative or friend, or association with their patients or through their research.

I don’t know anyone who hasn’t got a cancer story to tell, whether it is personal experience, a relative or friend, or association with their patients or through their research. Four infants in China have died and at least 53,000 are reportedly ill, many seriously so, having been fed milk powder contaminated with the industrial chemical

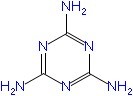

Four infants in China have died and at least 53,000 are reportedly ill, many seriously so, having been fed milk powder contaminated with the industrial chemical  It is becoming apparent that contaminated baby formula is not the only problem. Milk, ice cream, yoghurt, confectionery such as chocolates, biscuits and sweets, as well as any foods containing milk from China have been banned from import into Singapore after the country’s agri-food and veterinary authority found melamine in imported samples. Similarly, Taiwanese authorities seized imported products after notification of contamination from Beijing earlier this month. Japan has recalled various products. Canada’s Food Inspection Agency has warned citizens not to eat a dessert – Nissin Cha Cha Dessert – imported from China that has been found to be contaminated with melamine. The authorities in the Philippines are currently testing.

It is becoming apparent that contaminated baby formula is not the only problem. Milk, ice cream, yoghurt, confectionery such as chocolates, biscuits and sweets, as well as any foods containing milk from China have been banned from import into Singapore after the country’s agri-food and veterinary authority found melamine in imported samples. Similarly, Taiwanese authorities seized imported products after notification of contamination from Beijing earlier this month. Japan has recalled various products. Canada’s Food Inspection Agency has warned citizens not to eat a dessert – Nissin Cha Cha Dessert – imported from China that has been found to be contaminated with melamine. The authorities in the Philippines are currently testing. UPDATE:

UPDATE:  Melamine is an organic compound, a base with the formula C3H6N6. Officially it is 1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triamine in the IUPAC nomenclature system (CAS #108-78-1). It is has a molecular mass of just over 126, forms a white, crystalline powder, and is only slightly soluble in water. It is used in fire retardants in polymer resins because its high nitrogen content is released as flame-stifling nitrogen gas when the compound is burned or charred.

Melamine is an organic compound, a base with the formula C3H6N6. Officially it is 1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triamine in the IUPAC nomenclature system (CAS #108-78-1). It is has a molecular mass of just over 126, forms a white, crystalline powder, and is only slightly soluble in water. It is used in fire retardants in polymer resins because its high nitrogen content is released as flame-stifling nitrogen gas when the compound is burned or charred.