TL:DR – If you dissolve salt in water, you raise its boiling point. Similarly, you also lower its freezing point. These effects occur with any solute dissolved in any solvent and depend on how many solute particles are dissolved in the solvent. The key phrase is colligative properties.

Colligative properties include: Relative lowering of vapour pressure (Raoult’s law), elevation of boiling point, freezing point depression, osmotic pressure.

Colligative properties determine how a solvent will behave once a solute is added to make a solution. The degree of change depends on the amount of solute dissolved in the bulk liquid, not the type of solute. So, without my doing your homework for you…how does adding salt to water affect its boiling point? You will find several clues and several keywords above and below.

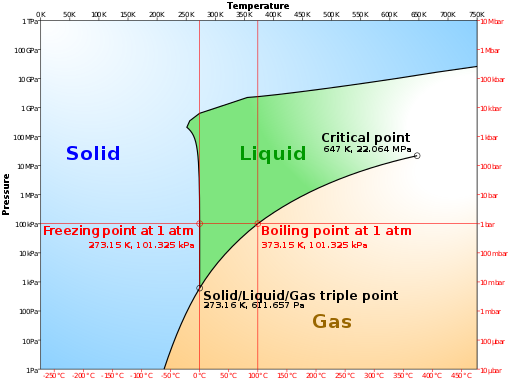

The fact that dissolving a salt in a liquid, such as water, affects its boiling point comes under the general heading of colligative properties in chemistry. In fact, it’s a generic phenomenon dissolve one substance (the solute) in another (the solvent) and you will raise its boiling point.

So, here’s a rough explanation of what’s going on. If a substance has a lower vapour pressure than the liquid (it’s relatively non-volatile in other words) then dissolving that substance in the liquid, common salt (NaCl) in water (H2O), for instance, will lower the overall vapour pressure of the resulting solution compared with the pure liquid. A lower vapour pressure means that the solution has to be heated more than the pure liquid to make its molecules vaporise. It is an effect of the dilution of the solvent in the presence of a solute. If you want to know about tungsten and why it is used in incandescent light bulbs please check out the Wikipedia entry.

Put another way, if a solute is dissolved in a solvent, then the number of solvent molecules at the surface of the solution is less than for pure solvent. The surface molecules can thus be considered “diluted” by the less volatile particles of solute. The rate of exchange between solvent in the solution and in the air above the solution is lower (vapour pressure of the solvent is reduced). A lower vapour pressure means that a higher temperature is necessary to boil the water in the solution, hence boiling-point elevation.

Conversely, adding common salt to water will lower its freezing point. This effect is exploited in cold weather when adding grit (rock salt) to the roads. The salt dissolves in the water condensing on the road surface and lowers its freezing point so that the temperature has to fall that bit more before ice will form on the roads.

A much more fun use for freezing point depression is to add salt to ice to make ice cream. The About site has some instructions on how to do this, although it’s probably not too tasty.

Curiously, at least one Sciencebase reader was searching for the phrase “how does sugar affect the boiling point of water?” and landed on this page. This is essentially the same question as, “does salt affect the boiling point of water?” The nature of the solute, the material being dissolved in the solvent, is pretty much irrelevant at a first estimate. Rather, it is the amount of material that is dissolved (which depends on the materials solubility) that influences the boiling and freezing points as described above.

Many people in the modern Western world delude themselves that their culture is generally free from the effects of intoxicating substances except in the criminal underworld, and that ‘nice people don’t take drugs’. But Richard Rudgley of the University of Oxford, a researcher of the oasis communities of Chinese Central Asia, shows that our culture and other cultures across the world have a rich tradition of using chemicals, mainly from plants, to produce altered states of consciousness. These range from the ritualistic use of the fly-agaric in Palaeolithic Europe to betel-nut chewing in Papua New Guinea, and from pretentious bone-china tea sets in Surbiton to the tragic inhaling of petrol fumes by Aboriginal Australians.

Many people in the modern Western world delude themselves that their culture is generally free from the effects of intoxicating substances except in the criminal underworld, and that ‘nice people don’t take drugs’. But Richard Rudgley of the University of Oxford, a researcher of the oasis communities of Chinese Central Asia, shows that our culture and other cultures across the world have a rich tradition of using chemicals, mainly from plants, to produce altered states of consciousness. These range from the ritualistic use of the fly-agaric in Palaeolithic Europe to betel-nut chewing in Papua New Guinea, and from pretentious bone-china tea sets in Surbiton to the tragic inhaling of petrol fumes by Aboriginal Australians.

Our sense of smell is much better than we give it credit for. A report in Nature Neuroscience puts paid to the notion that the human reputation for having a poor sense of smell compared to other animals.

Our sense of smell is much better than we give it credit for. A report in Nature Neuroscience puts paid to the notion that the human reputation for having a poor sense of smell compared to other animals. More than forty research papers highlight the effects of emerging contaminants on human health and the environment in the December 2006 issue of the journal Environmental Science & Technology, among their number are reports on nanoparticles, pharmaceuticals, disinfectant by-products, and fluorochemicals.

More than forty research papers highlight the effects of emerging contaminants on human health and the environment in the December 2006 issue of the journal Environmental Science & Technology, among their number are reports on nanoparticles, pharmaceuticals, disinfectant by-products, and fluorochemicals.