There are many educational and ethical issues regarding the environment and environmentalism that are generally not addressed, especially when it comes to teaching non-science students. Independent environmental services professional and college professor Chyrisse P. Tabone, who is based in Tampa/St. Petersburg, Florida has spent several years attempting to find a way to remedy this situation.

Sciencebase covered her work on teaching environmental science some time ago, now in this post we put a few questions to Professor Tabone about her follow-up paper in which she examines a new approach to teaching environmental issues and the responses of a group of students confronted with those problems.

What is the basis of your approach?

I have honed and perfected my non-traditional teaching instruction using “cognitive dissonance” as a motivator and educational tool for the last six years. Creating a purposeful use of dissonance in the classroom is probably the antithesis of traditional pedagogical instruction. However, I believe its cutting edge tactic melds perfectly with the “science/technology/science” approach to science education.

What is cognitive dissonance and how does it relate to issues that cause “upset”?

Cognitive dissonance was first described in “When Prophecy Fails” by Leon Festinger in 1956 after profiling and researching a UFO cult in the Midwest. Basically, it is the “emotional pang” or dissonance one feels when observing or experiencing something that goes against one’s moral or ethical grain. It is that nagging feeling or disgust one feels when hearing something that utterly collides with one’s upbringing or inner core values. One can react to such dissonance by either justifying the act or actively pursuing change to “make things right”. I have seen the “Theory of Cognitive Dissonance” applied to research relating to criminology, marketing, and nursing but not in the field of education.

What first turned you on to cognitive dissonance as an approach to teaching environmental science?

As a little bit of history, I had the epiphany about using cognitive dissonance as an educational tool one day while opening a piece of mail from PETA. I was formerly a member and got tired of opening mail with photos of abused, caged, or tortured animals. I notice that a lot of groups (even Doctors Without Borders) use these photos to provoke cognitive dissonance so people react as follows: 1) write a cheque or 2) rationalize the situation in one’s head and do nothing. This is why my model is critical to research. It confirms the elements and supports what Festinger (Theory of Cognitive Dissonance) and Lerner’s (Belief in Just World) theories were trying to say!

Where did you test the theory?

The study was performed at a private suburban liberal arts college with a multicultural cross-section of traditional and non-traditional students. The students at the college are required to take a science course for their degree programs and environmental science is offered as this option. Most of the students enter the class with dread and disdain based on prior experience with science or earth science courses taken in high school. They ask “Why do I have to take this stinking science course? I am a [blank] major.” The challenge to an instructor is “How do I motivate non-science majors to like science, especially environmental science?” The ramification of this study exceeds the classroom and enters into mainstream society which is essentially a group of “non-science majors”!

What environmental issues were raised with the group and in what way?

The course consisted of lectures on traditional environmental science and public health topics (required content for the course) through the use of open discussions, films, and YouTube news clips interspersed throughout the four-hour weekly class. Since the tone of the class was often dissonant during serious discussions, humour (e.g. silly animal photos embedded in a serious lecture or moment, “redneck” recycling photos) was invoked to offer a pressure relief valve. The course is really a roller-coaster ride.

What examples of topics were discussed during the study?

We looked at the use of depleted uranium in Bosnia/Croatia, Afghanistan, and Iraq (the film “Poison Dust”). The CHEERS pesticide study in Jacksonville, Florida (about three hours from the college). A contaminated African-American neighbourhood in Brooksville, Florida (about 1 ½ hours north of the college). I gave the students a lot of personal anecdotes since I did pro bono work for the community. We studied the movie “Climate change – An Inconvenient Truth”, which was a real eye-opener for students that can get past having Al Gore as the narrator. Some have bought into the Fox News rhetoric. We investigated the case of a local man who got hassled for installing a plastic lawn, students get very emotional when discussing a grandfather thrown in jail for not wanting a brown lawn.

Were there any other topics?

We also discussed: the case of a local woman who owns a string of apartment complexes arrested for knowingly using unskilled labour (homeless) people to remove asbestos, a known carcinogen, from her buildings; the controversy of Teflon and PFOA, a Class B carcinogen, still being used in products without a warning label; the effects of radiation after Hiroshima and Nagasaki; white phosphorus weapons in Iraq; the bedbug epidemic, the BP oil spill; fracking (the movie “Gasland”); healthcare in the world (the movie “Sicko”).

With what did you task the students?

Students wrote Reaction Papers every week describing their emotions of “disgust” or “anger” with the topics we discussed. Qualitative data was acquired from the reaction papers and observations during classroom discussions. Keywords and themes were derived from the data. Overall, the students seemed to be more interested and moved by the “planted” experimental topics rather than the obligatory mundane science content which was required to meet course objectives.

What, then, does it take to interest students?

Real-world connections, personal relevance and societal relevance! A local story of groundwater contamination means more to a student than contaminated groundwater in a Third World Country. Students relate to facts affecting their personal life-home, family, and health. After doing the “cold memory test” at the end of the school term they recalled the topics which affected them as well as seeming to tie these “memories” to the required science content.

That’s a positive, but does the approach have a lasting effect?

I have bumped into former college students years later who told me “I loved your class. It was never boring. The discussions were great.” When I quizzed them asking, “O.K. What do you remember from the class?” They could actually recite a “laundry list” of topics we studied and discussed. It was very impressive and rewarding as an educator to experience this.

Other than improving understanding does the course affect the students’ daily lives?

During the course (and after) students have expressed sharing information with friends and family, particularly their children. They also get interested in conservation of water at home, recycling at home and even starting programs at work. Some get involved politically, join environmental groups and online networks. I have had students change their major or minor in environmental science after taking the course. I ran into a former interior design student who proudly told me she is designing “green” and incorporating environmental sustainability into her designs. I have seen former students at rallies and protests concerning political causes.

So, conventional approaches are failing, where this approach succeeds?

Traditional environmental science teaching of the “Amazon rainforest, extinction of panda bears or polar bears, and volcanic eruptions” kind do not motivate students to learn more about science. Not discussing current events or shying away from controversy is doing a disservice to the students. Discussing the “elephant in the room” or what educators deem as the “null curriculum” is even more critical today since science has become politically charged. It is important that students, especially non-science majors, have exposure to these topics in a safe, academic setting where they can be thoughtfully presented and discussed.

How do you define a controversy for use in education?

My research set out to define the elements of a controversy and allow the students to “react” to a slew of introduced environmental science and public health topics. Certain topics stood out as “controversial” because they had the key defining element-injustice. Topics concerning injustice, particularly in relation to intentional afflict/abuse, absence of freedom, ignorance, inequality, neglect, and greed stir people’s emotion and evoke degrees of cognitive dissonance. To awaken a student or non-science person, you must get their attention first. Using cognitive dissonance as an educational tool does this.

Does it work for all students?

Most students enjoyed the course and seemed to gain an interest except a minority of self-proclaimed politically conservative students. They reacted in classic Festinger cognitive dissonance fashion by clinging to their scientific misconceptions. These students became even more entrenched in their misconceptions by becoming argumentative at times and hostile in classroom discussions. As Festinger noted, it is much easier to justify a misconception or hang with like-minded people to support a flawed notion than to give up the notion.

Tabone, C. (2011). Controversial issues in an environmental science course: how do students respond? Interdisciplinary Environmental Review, 12 (3) DOI: 10.1504/IER.2011.041818

Tabone, C. (2011). Controversial issues in an environmental science course: how do students respond? Interdisciplinary Environmental Review, 12 (3) DOI: 10.1504/IER.2011.041818

There’s a cute video montage currently doing the rounds in which a re-working of the Billy Joel song “We didn’t start the fire” reminisces about growing up in the 1970s and the 1980s and cites the countless games, toys, TV shows and other cultural references we had during that time years before anyone had an iPad, mobile phone or other essential gadget. Featured is the Rayleigh Chopper bicycle, Atari video games, Tiswas, and Swap Shop (it’s very British, did I already say?). Most of the references are positive but a few things are missing the ever-present mutually assured destruction and the threat of nuclear war and in those pre-climate change times when were knew about greenhouse gases but were worried about the coming Ice Age, there was acid rain.

There’s a cute video montage currently doing the rounds in which a re-working of the Billy Joel song “We didn’t start the fire” reminisces about growing up in the 1970s and the 1980s and cites the countless games, toys, TV shows and other cultural references we had during that time years before anyone had an iPad, mobile phone or other essential gadget. Featured is the Rayleigh Chopper bicycle, Atari video games, Tiswas, and Swap Shop (it’s very British, did I already say?). Most of the references are positive but a few things are missing the ever-present mutually assured destruction and the threat of nuclear war and in those pre-climate change times when were knew about greenhouse gases but were worried about the coming Ice Age, there was acid rain. Exergy is perhaps an unfamiliar concept. Energy we can fairly easily get to grips with, it’s a measure of the ability of a system to do work. Work is what causes a system to change its energy state…hmm…first law of thermodynamics. But, what is exergy and where does it fit into the energy equation?

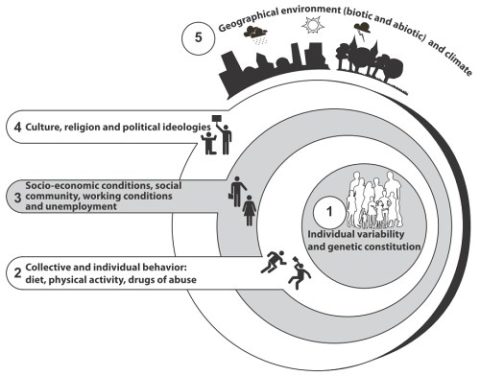

Exergy is perhaps an unfamiliar concept. Energy we can fairly easily get to grips with, it’s a measure of the ability of a system to do work. Work is what causes a system to change its energy state…hmm…first law of thermodynamics. But, what is exergy and where does it fit into the energy equation? Live fast, die young. You’re a long time gone. Sleep when you’re dead. The hedonists mantras. Lifestyle choices whether in terms of food consumption, alcohol and drugs or sexual activity are down to the individual. Nannying by governments, who have their own mantras: Smoking Kills, Know your limits, Get your five-a-day, Use protection, etc, all costs money, is apparently ignored by most people, and probably has little effect on those lifestyle choices.

Live fast, die young. You’re a long time gone. Sleep when you’re dead. The hedonists mantras. Lifestyle choices whether in terms of food consumption, alcohol and drugs or sexual activity are down to the individual. Nannying by governments, who have their own mantras: Smoking Kills, Know your limits, Get your five-a-day, Use protection, etc, all costs money, is apparently ignored by most people, and probably has little effect on those lifestyle choices.

Environmental science is about as politically charged a discipline you might find, stem cells GMOs, vaccines, and nuclear energy notwithstanding. In some circles, particularly certain sectors of academia and the media, environmental discussions are synonymous with controversial debates.

Environmental science is about as politically charged a discipline you might find, stem cells GMOs, vaccines, and nuclear energy notwithstanding. In some circles, particularly certain sectors of academia and the media, environmental discussions are synonymous with controversial debates.