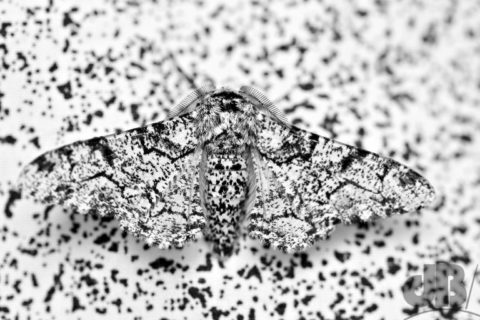

A Peppered Moth, Biston betularia, was drawn to my scientific moth trap last night. This species is probably the most important moth, scientifically speaking. It’s something of a Victorian scientific hero, in fact, and a speckly example of how evolution doesn’t always need millions of years to happen, but can take place within a decade or so if not faster.

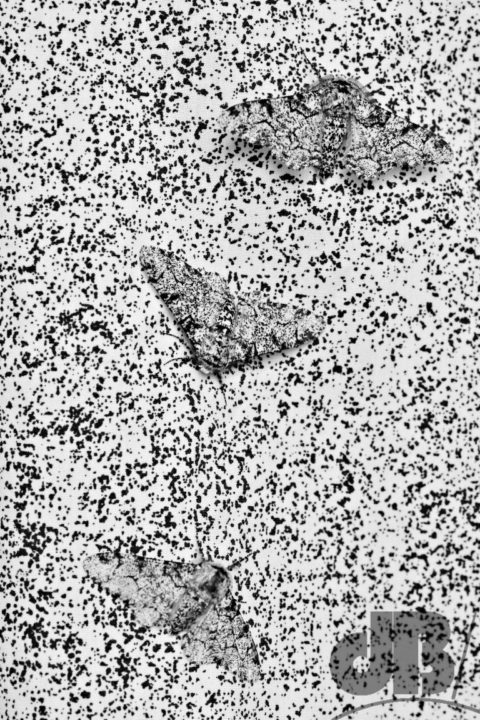

During the sooty days of the Mancunian branch of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, this creamy white moth with black peppery speckles evolved to an almost black form (Biston betularia betularia morpha carbonaria). Originally, the light form had been well camouflaged on lichen, which meant it was hard for birds to see and so safe from becoming avian lunch. But a lot of the lichen was killed off by the smoke and smog of the industrial revolution and coated with soot. Those mainly white Peppered Moths were no longer well camouflaged and were easy pickings for birds.

However, a mutation arose in this species that for all intents and purposes gave rise to a melanic, dark, form of the moth. No more bright white but a sooty black moth that was now camouflaged on the dark surfaces of the industrial era. Now, the dark moths that evaded detection by birds could live to breed and pass on their genes for this melanism. It seems that the mutation arose around 1819 as the carbonaria form was not noted by naturalists before this date.

The rapid change from a bright to a dark, melanic form, industrial melanism as it is now known, provided evidence of survival of the fittest, natural selection, and evolution in action. By the end of the century, 95 per cent of the Peppered Moths in Great Britain were carbonaria.

The melanic form began to decline in Britain after the Clean Air Act of 1956 when smokeless fuels came to the fore and uncapped pollution was no longer acceptable. I am yet to see the melanic form, hence the lack of photos, but it certainly still exists in the wild. This reversal of the adaptation lends additional support to the evidence for the original industrial evolution.

There was some concern in the 1990s that the original research proved nothing as it didn’t take into account the moth’s natural resting places and that moth migration might skew the actual results and may have led to some of the effect. However, interesting research by the late Michael Majerus discussed and followed-up here in the journal Biology Letters provides strong evidence that reinvigorates the original hypothesis of industrial melanism in the context of predation by birds.

The authors talk of how “caveats about the predation experiments discussed in Majerus’s book, critiques by other biologists, as well as points made particularly forcefully in a review of the Majerus book, were soon exploited by non-scientists to promote an anti-evolution agenda and to denigrate the predation explanation”. They add that “both the public in general and even evolutionary biologists began to doubt the bird predation story.”

Their paper also debunks the creationist ideas that arose when doubt was first cast on the idea of this rapid evolution of an animal as its surroundings changed through industrialisation and into the post-industrial world of the North of England. Moreover, industrial melanism is seen in other types of moth and provides parallel evidence for the changes observed in the industrial evolution of the Peppered Moth.