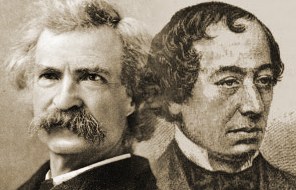

Whose line is it? Nineteenth century British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli supposedly remarked that there are “lies, damned lies and statistics.” Although often cited, we have no evidence that the phrase originated with Disraeli. A more likely possibility is that it originated with an American author, with Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain. Regardless of its origin, the phrase implies that the manipulation of statistics is so easy that their use is tantamount to telling the worst kind of lie.

Whose lies, Twain’s or Disraeli’s?

In science circles we hear regularly of the misuse of statistics, in the media, down at the pub, and in some cases by scientists themselves. But, argues Richard Hamilton of The Mershon Center, at Ohio State University, in Columbus, although stats might be manipulated, it is much easier to lie without them. Writing in IJBG, Hamilton suggests that, “With the constraint of evidence removed, an author can proceed unhindered to the declaration (or revelation) of a preferred ‘truth’.” He argues that there is a disconnection between the two branches of intellectual endeavours, the discovery/ research and the reporting/ dissemination. He believes that in the works of many popular writers, biographers, historians, social scientists, journalists, and freelance commentators the connection is often broken. He says that assertions are being made and “facts” stated with little research to support them and that these “declared truths” are a serious problem.

Part of the problem is that declared truths are made about human society, our beliefs and behaviour, especially in the context of history, without the recognition that while today we have access to enormous quantities of data on public opinion, prior to the 1930s, with rare exception we had essentially no credible information on the attitudes or the actions of “the masses”. We have, for example, no real knowledge of how close families were in New York City up to the 1830s at which point, according to commentator Alexis de Tocqueville, family values collapsed. Some accounts have it that the Great War was a response to popular opinion, to “strong anti-Serbian feeling [among the public] in Austria-Hungary.” This too lacks evidence, no one had polled “the people.”

We have one striking exception, this involving the storming of the Bastille in 1789. Many accounts have it that “Paris” rose in arms. But in this case we have some evidence, the participants having been given a certificate attesting to participation. The number, sometimes referred to as the “sacred nine hundred,” would have formed about one percent of the city’s possible contenders. Most Parisians, apparently, were doing something else on that famous day.

To repair the disconnection between research and reporting, we must discard those deceptions, the declared truths. On many occasions, the most honest intellectual stance for an author is an easy one, a simple statement–I don’t know.

![]() Hamilton R. (2013). Things not known, Int. J. Business and Globalisation, 10 (3) 233-244. DOI: 10.1504/IJBG.2013.052985

Hamilton R. (2013). Things not known, Int. J. Business and Globalisation, 10 (3) 233-244. DOI: 10.1504/IJBG.2013.052985