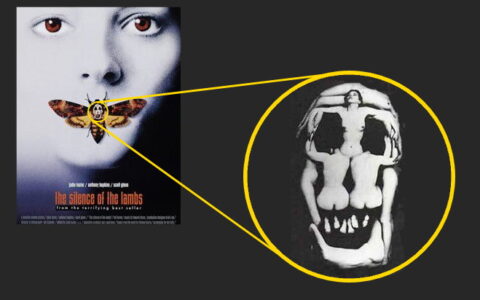

A few days ago I tweeted about a famous picture of a moth, the Death’s Head Hawk-moth used in the artwork surrounding the 1991 psychological thriller “The Silence of the Lambs”. At first glance, the moth looks genuine, but closer inspection reveals that what is thought of as markings resembling a skull on the moth’s thorax is, in the movie illustration, actually an imprint of a well-known 1951 creation of Salvador Dali and photographer Philippe Halsman.

In that image, In Voluptas Mors, a group of naked women were posed in such a way as to create the illusion of a skull. Of course, this morbid allusion fits perfectly with the theme of a murderer who skins his female victims in the movie. The women are lambs to the slaughter, their fleeces flayed from their bodies by the serial killer and a symbolic moth placed on their tongues to silence them forever.

Although a representation of the Death’s Head Hawk-moth (Acherontia atropos) features in the promotional materials for the film. Fellow science writer Rowan Hooper reminded me that in the movie itself, it is the pupae of a different moth, the Carolina Sphinx Moth (also known as the Tobacco Hawk-moth (Manduca sexta) that feature in the plot. In our chat, I mentioned that I wasn’t particularly interested in moths when that movie was first on release, but he said he was very much interested in Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) at the time, Indeed, Hooper was specifically working in research trying to figure out something rather odd about Lepidoptera.

It turns out that the males of all Lepidoptera, all 180,000 species of moths and butterflies produce two types of sperm. They make sperm that carry their genetic material, their DNA, in the sperm’s nucleus, so-called eupyrene sperm, but they also make sperm that lack that DNA, apyrene sperm, or parasperm. Indeed, at least half of the sperm are blanks. In one type of swallowtail butterfly, 90 percent of the male’s sperm lack DNA. That percentage is 96 in Manduca sexta. Even more bizarrely, Lepidoptera are the only creatures that do this.

Obviously, the fusion of sperm with egg is fundamentally all about fusing the genetic material from the male with that of the female to fertilise the egg and create offspring from both parents. So, why would males make sperm that contain no genes to pass on and more to the point would be incapable of fertilising the female’s eggs. To cut to the money shot: nobody knows, for sure.

There are hypotheses, of course. It might be that the blank sperm act as some kind of useful filler, inactive biological padding. The blanks perhaps take up the female’s resources somehow while the active sperm do their job. Maybe this precluded further matings with other males ensuring that the first male’s active sperm are the ones that fertilise her eggs. Alternatively, perhaps Lepidoptera females have defences within their reproductive tract to ensure that only the fittest sperm reach their eggs and so the males produce these blanks as decoys (after all blanks would require fewer material resources and energy to produce, if many are going to be wasted). An alternative theory might be that the blank sperm are some kind of nuptial gift for the female, not so much inactive filler as nutrients.

There is evidence that a gene known as Sex-lethal (Sxl) is involved in the production of apyrene sperm in Lepidoptera. A paper in PNAS looked at the activity of this gene in the Silk Moth, Bombyx mori, and found that it was partially responsible for the generation of apyrene sperm. Moreover, the team showed that apyrene sperm have to be present in the male moth’s ejaculate to allow the active eupyrne sperm to travel from the female’s genital opening, the bursa copulatrix, to her spermatheca (where she stores sperm prior to egg fertilisation).

So, while no definitive answer is known for all Lepidoptera that produce eupyrene and apyrene sperm, for the Silk Moth at least it seems that firing blanks is the best way for the active sperm to hit the target.