As of 9th September 2019, I have tallied more than 10000 moth specimens of approximately 300 different species via the scientific trap. I started trapping this year on 20th February and there have been a few short breaks for holidays in between lighting-up sessions. And then there was the outage when I smashed the UV light…

These numbers represent a tiny fraction of the total number of moths that will have passed through our garden in that time and the species count is barely 12 percent of the total number of species in the British Isles.

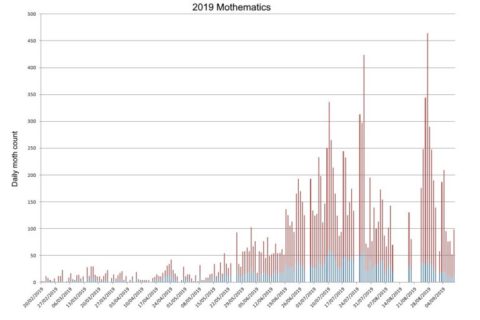

The red barchart shows the peaks and troughs of total numbers counted after each trapping session. Going from blanks some mornings to a handful in the winter months and into spring and then peaking with several hundred of a few dozen different species at various times during July and then late August (when we had a very hot spell with Cambridge breaking temperature records).

The blue of the chart shows the species count for each session. This peaked on 10th July with 60 different species, and perhaps more micro moths that I am too inexpert to have tallied on the day. There were 276 specimens in and around the trap come the morning of that day. The biggest tally was 27th August with 421 moths of some 43 different species.

For a complete listing of all species with vernacular and scientific names and, of course, record shots of each, check out my Mothematics Gallery on Imaging Storm. I’ve logged 321 moths species (most of them during the period July 2018 to September 2019 and most of those using the garden trap. A dozen or so in the gallery were photographed elsewhere.

I wrote about why scientific moth trapping is an important endeavour earlier in the year and how the modern amateur approach involves releasing the moths alive once tallied/photographed. Someone claimed that there are hundreds of thousands of people mothing. There aren’t. But, given that a single pipistrelle bat eats around 300 flying insects every night it is easy to see that in a country village where there might be three or four people trapping regularly, the bats are taking far more moths out of circulation than moth-ers.

As you can see from this small selection of my photos, moths are anything but grey and beige. Many fly during the day, many are brightly coloured, some are just sex machines (they don’t have mouthparts and don’t eat), all of them from the humblest micro to the biggest we have in the UK, the Privet Hawk-moth are astonishing examples of biological diversity in the invertebrate world.