For a lot of people, moths are tiny, fluttery creatures that turn to dust if you try to catch them and whose caterpillars can chew through their vegetable patch, their prize perennials, and even their carpets and clothes. Now, there are pest species, admittedly, and these can to some extent be controlled in appropriate conditions. However, for those who have been initiated into the wonders of the Lepidoptera, the 180,000 different species around the world are a natural wonder to behold.

For those of us who do get hooked on moths – we call ourselves “moth-ers” by the way – it can become an obsession that persists from the first very first lep sighting. For those who insist that moths and butterflies are somehow different, and that butterflies are far more beautiful and far more worthy of our attention, it’s worth pointing out that all butterflies are just a single group within the Lepidoptera.

The other groups include the noctuids (also known as owlets), the geometers (their caterpillars, larvae, measure the earth, they’re the inchworms), the sphinx moths (also known in the British Isles as the hawk-moths), and several others. Butterflies are merely one such group among the moths. Moreover, they’re actually just one group within the so-called “micro moths” (nothing to do with size, everything to do with their place on the evolutionary tree).

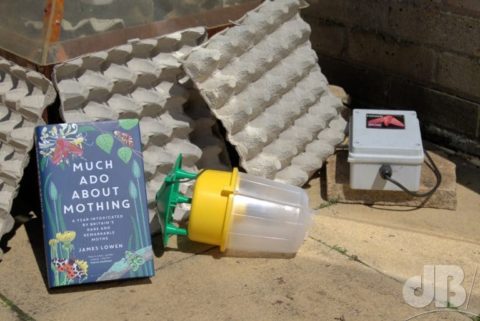

It’s complicated, and all moth-ers come to the obsession through a different route. In his wonderful new book, Much Ado About Mothing, James Lowen, challenges all those dusty preconceptions about moths. He takes us on a lavish and circuitous route around the UK searching for the rarest and most intriguing of our scaly-winged insects. Incidentally, of the 180000 worldwide species a mere 2500 or so are found in the UK, some of them migrants and rare visitors.

With Lowen, we clamber up mountains, we wade through marshes, and we look for what lurks in the wood and on the trees in ancient woodland. What we find is an incredibly diverse group of animals, all of them sharing common features but each very different from the next. Lowen shows us just what most people seem to miss about moths – their natural beauty.

Mothing, as a hobby, is on the rise. It has often been a parallel hobby for birders, one that can be done with lures and lighttrap or even just a white sheet and a bright torch, in one’s own back garden or a local patch of countryside, and…even right in the centre of the city! Your mileage may vary on what you find, but each mothing experience brings new delights, and a new hope that the next lep to turn up will be one of the rarest of the rare or perhaps even one once thought extinct that turns out to be very much extant.

If you are not yet convinced, then delve into Lowen’s book, it will astonish and intrigue even the hardiest of mottephobe, I am sure. And, remember butterflies are just one group within the moth family…and who doesn’t like butterflies?

If you love or loathe lepidoptera buy this book, Lowen’s wonderful enthusiasm will give you a mental boost either way and if you were indifferent to the scaly-winged insects, it might even let an interest pupate and to take to the air.