Our brains seem to be wired to find patterns, we see elephants and castles in the clouds, imps dancing in the flames of an open fire, and we all know the man in the moon. The phenomenon is known as pareidolia.

Pareidolia - The perception of a recognizable image or meaningful pattern where none exists or is intended, as the perception of a face in the surface features of the moon.

It is the existence of a face where no actual face exists that is perhaps the most intriguing form of pareidolia. That mountain range on Mars, Cydonia, that seems to be a mask has taunted conspiracy theorists for decades who imagine it as some kind of giant alien conurbation.

But, a mere two dots, a short line, and a curve will make us smile :-)

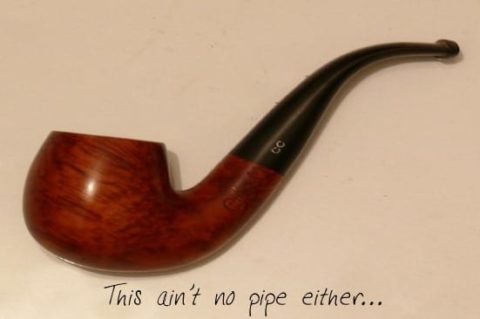

This is pareidolia in action, in fact, the whole of visual art is, in some sense, relying on the phenomenon. As Rene Magritte remarked: ceci n’est pas une pipe. Indeed, of course, it’s not a pipe, it’s pigments and paints smeared on a canvas with a bristle-ended stick to generate something that when we view it, puts us in mind of smoking paraphernalia, specifically, a pipe. Just as those cave paintings of buffalo and prehistoric hunters are not the actual buffalo nor the spear-wielding hunters.

Nature, of course, got there millions of years before artists. There are countless organisms that are patterned in such a way to camouflage themselves in their natural environment. They aren’t their environment, but to an approaching predator with similar wiring in its brain that confuses us, they perceive that leafy stick insect as nothing more than a leaf rather than a snack. Similar a Lime Hawk-moth looks like nothing more than a leaf, inedible to most carnivores that avoid salad.

Other organisms make faces. Moth and butterfly larvae, also known as caterpillars, for instance, might have spots and splodges, that look like eyes and that coupled with their overall shape and movements might make them look like a venomous snake that a bird would best avoid pecking.

The adult morphs of caterpillars often use a similar trick, there are countless Lepidoptera that have “eye spots” on their wings that might remain hidden and so unattractive until the butterfly or moth is startled and then a quick opening of those wings reveals the hunter within to deter the snacking predator.

Today’s haul of moths to the Sciencebase actinic light trap, brought with it the usual range of May-June fliers: lots of Heart & Darts, Setaceous Hebrew Characters, Lime Speck Pug, Light Brown Apple Moth, Common Pug, Treble Lines, Vine’s Rustic, Minors, Garden Carpet, Light Brocade, Shuttle-shaped Dart, Turnip Moth, Flame Shoulder, Common Swift, Willow Beauty, Cabbage Moth, and Rustic Shoulder Knot. Most of these are camouflaged to hide among leaf litter or resemble fragments of bark. The Lime Speck is an exception, it looks like a tiny splat of bird droppings (another example of pareidolia).

An Eyed Hawk-moth (Smerinthus ocellata) was in the trap this morning too, it is a large and wonderful creature. It looks like a leaf when it’s perched at rest, but agitated it will open its wings to reveal a pair of, you guessed it, eyes! They can stare back at you and most predators would be startled enough by the appearance of such a face that they would run or take flight rather than risk being eaten themselves.

This specimen was very calm, wings closed up for the photoshoot, unfortunately. But, it hopped on to my hand at one point and as it crawled around and tickled my palm it began to warm and gave me a quick wink before taking flight and heading back to whatever hiding place it might find before nightfall.

In all this talk of pareidolia and obvious question comes to mind, why are our eyes so easily fooled, why did we evolve to be so readily suckered by some colourful splodges that happen to sit a distance apart? Why do we see faces everywhere we see two spots together? Well, predator-prey evolution is a game of cat and mouse, to coin a phrase. Animals evolved to be able to recognise faces. We know a face when we see one as does presumably every other higher organism.

In natural selection, those prey organisms that successfully reproduced and passed on their genes were the ones that evaded predation before they had a chance to procreate. An adaptation such as resembling a face and so possibly a larger animal that might fight back would offer that great survival of the fittest benefit to the offspring that inherited it. We usually know when pareidolia is happening. But, a Blackbird approach a tasty morsel of Lepidoptera presumably sees the Peacock butterfly flashing its eyes and assumes the worst.

I say we know, but we can never shake off the feeling that those eyes really are looking back at us whether it’s an animated emoji, the snarling rear lights of a Japanese car, or those Martians in that giant conurbation who are right now watching us keenly and closely as we might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water…