Worried about keeping your private details private on Facebook? Do you know what information Google stores on each and every search you do? What about your bank, do they track your online purchases and send that information to direct marketing agencies? These are all questions each and every one of us should know and want the answers to, but privacy issues are not clearcut. As more and more social interaction takes place on the Internet they have to be addressed. But, who, when, and how?

There is currently no common framework for communicating and discussing privacy issues, according to Nicholas Harkiolakis of the information technology department, Hellenic American University, in Greece. He hopes to change all that and has introduced the concept of an Information Privacy Unit (IPU). But, why should we worry about something so seemingly esoteric?

Well, Professor Harkiolakis has been involved in software development for a quarter of a century and has focused on applications in business and academic settings where issues of privacy are paramount. With the advent of the internet, we have seen an explosion in social interaction that crosses borders and allows people to communicate in ways that were undreamt perhaps as recently as when Harkiolakis began his career in IT. Social structure is changing from the level of the individual to corporations and to governments. “We have seen a major shift in power regarding control of personal data from the individual to public organisations and public bureaucracies,” Harkiolakis says.

He points out that companies that hold databases of personal information from our banks and clubs to internet service providers, websites and search engines are monitoring us all with very little regulation, and that is not taking into account the illicit monitoring of organisations of which we may not even be aware, such as those that infiltrate our computers with spyware and other nasties. “Other forms of monitoring could eventually be used to discriminate against individuals,” adds Harkiolakis, “not because of their past but because of statistical expectations about their future.” In particular, he says, we are simply unaware of what personal data has been captured and how it might be manipulated and used against us in some shape or form. If we, says Harkiolakis, we would never allow that data to be captured in the first place.

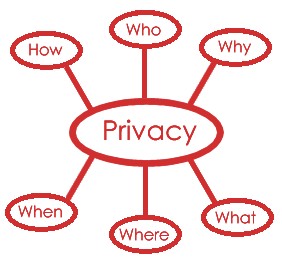

Writing in the International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialisation (2007, vol 6, 56-63) in a special issue on data protection, trust and technology, Harkiolakis explains the possible ways of addressing privacy concerns. He suggests that there six angles, or dimensions, to privacy that basically follow the journalistic mantra of What, When, Who, Where, Why and How. By taking this six-dimensional approach to privacy, Harkiolakis explains that it becomes possible to define strict guidelines for implementing privacy policies, specifically within software that will act as mediators (in web browsers, for instance) or as representatives (in other programs and on computer servers) between you, the user, and the proverbial them.

Cyberspace is vast, the amount personal information “out there” is enormous, just look at the rapidly growing number of web pages, ecommerce sites, Facebook and MySpace users, Diggers, bloggers and others. This growth has multiplied our abilities to manipulate and aggregate information beyond imagination, terabyte upon terabyte of data oscillates across the wires. Now that exchanging data across these wires, fibre optics, and satellite connections is entirely the norm and so privacy is a significant issue. The six-dimensional approach to privacy proposed by Harkiolakis looks at the manipulation of data from six different angles: Personal data (What) would have been collected with a variety of methods (How) by different entities (Who) at different times (When), at different websites or servers (Where) and for different purposes (Why). In a dispute, legal or otherwise, an investigation of each of these points in the transaction or use of data would allow both parties to examine whether any breaches of privacy, trust, or the law was made.

A breach at any of those six points would represent a breach however you look at it. Conversely, by developing software that can analyse and assess each of these individual dimensions and how they mesh together during a transaction it might one day be possible to produce a program, a browser plugin, for example, that monitors your activity on the Internet for you and warns you much more effectively than displaying a locked padlock in the status bar when a transaction is about to compromise your privacy.