Colourful language usually refers euphemistically to the kind of expletives and oaths you hear in a barrack room brawl. But, in the context of technology it could be the next big thing in colour printing.

Colourful language usually refers euphemistically to the kind of expletives and oaths you hear in a barrack room brawl. But, in the context of technology it could be the next big thing in colour printing.

Colour and natural language experts at Xerox have been working on what sounds like an entirely new way to get the best out of your digital photos. Their research could allow you to talk to your printer and tell it to “make the green a ‘mossy’ green” or “make the sky more sky blue”. More technically, you might one day be able to do all the kinds of colour and contrast corrections that are usually the preserve of programs like Photoshop, with simple phrases sent to the printer itself.

The approach speed up the workflow for graphic artists, printers, photographers and other image professionals and their assistants who could save time side-stepping the on-screen fine tuning process of printouts.

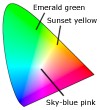

“You shouldn’t have to be a colour expert to make the sky a deeper blue or add a bit of yellow to a sunset,” research leader Geoff Wolfe says. The software is still in the development stages, but works by translating human descriptions of colour – “emerald green”, “brick red”, “sky-blue pink” – into the precise numerical codes printers use to control the amount of each primary colour they deposit at a single point in the printed image.

“Today, especially in the office environment, there are many non-experts who know how they would like colour to appear but have no idea how to manipulate the color to get what they want,” Woolfe adds. Moreover, the vast majority of computer screens in “non-expert” offices are setup incorrectly for screen to print comparisons and so cause the whole gamut of problems when a document that looks okay on screen is printed. Simple commands to rectify such issues avoid the problem of having to know how to set up the screen and ambient lighting.

Woolfe’s discovery could mean that colour adjustments can be made on devices like office printers and commercial presses without having to deal with the mathematics. For instance, cardinal red on a printer or monitor is really expressed by a set of mathematical coordinates that identify a specific region in a three-dimensional space, which is the gamut of all the colours that the device can display or print. To make that colour less orange, the colour expert distorts (morphs) that region to a new region in the gamut.

The ability to use common words to do this gamut morphing and adjust colour would have far-reaching implications for non-experts as well as graphic artists, printers, photographers and other professionals who spend a significant amount of time fine tuning the colours in documents.

“In the end it’s all about usability,” Woolfe adds, “Colour is so prevalent today, you shouldn’t have to be an expert to handle it.”